Some time ago, someone called me a “cranky old man.” Now it so happens I am exactly the same age as Donald Trump (and Ronald Reagan, at the time he became president). So I decided to take it as a compliment.

The reason why Mr. X paid me the compliment was because I have written, in a forthcoming book, that the US armed forces, along with the remaining Western ones, had gone soft. As did the societies in which those forces are rooted. Understandably the idea that wealth, highs standards of living, and luxury can cause one’s people to go soft is not popular in the countries in question. That is precisely why I want to explore it a little further here.

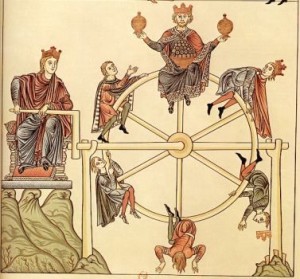

From Lycurgus, Solon, Heraclitus, Herodotus, and Plato on, many ancient statesmen, philosophers and historians believed that history was cyclical. Rise and fall, rise and fall. Repeated over and over again. Medieval sages such as Honoré Bonet and, in the Islamic World, Ibn Khaldun agreed. So did some twentieth-century scholars such as Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee. The details vary from one thinker to the next. But the gist of the argument is always more or less the same; if ever there was a topos, (Greek, singular of topoi), meaning a theme or archetypical story that people keep telling themselves, this is it.

As this particular topos goes, originally war was waged by men of poor, nomadic tribal societies like those of which, long ago, all of us used to be a part. At first they fought over such things as access to water, hunting- and grazing ground, domestic animals, and, not least, women. At some stage one tribe, often headed by a particularly able leader, defeated all the rest and united them into some kind of league, confederation, or federation. As the ancient Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Huns, Magyars, and Mongols all did.

As this particular topos goes, originally war was waged by men of poor, nomadic tribal societies like those of which, long ago, all of us used to be a part. At first they fought over such things as access to water, hunting- and grazing ground, domestic animals, and, not least, women. At some stage one tribe, often headed by a particularly able leader, defeated all the rest and united them into some kind of league, confederation, or federation. As the ancient Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Huns, Magyars, and Mongols all did.

Next, the victors took on their richer, settled, neighbors. They fought, triumphed, conquered, and subjugated. Having done so, they discarded their nomadic traditions and took up life in the cities under their rule. Exploiting the labor of others, they grew rich and soft. They also indulged in every kind of luxury, allowed themselves to be governed by women, and witnessed a sharp decline in fertility.

Having abandoned the military virtues, at some point they started looking down on them. Hiring foreigners to fight in their stead, they ended by losing the qualities that had made them great. Attempts to substitute technology for fighting power, such as were made both in fourth-century AD Rome and, repeatedly, in China, did not work. Nor is there any reason why they should, given that the barbarians could often capture or imitate the technologies and find renegades to operate them. As, for example, Genghis Khan and Timur did. Each empire in turn was overrun by its poorer, but more virile and aggressive, neighbors. More often than not subject peoples, long oppressed, rose and joined the invaders. The end was always the same: ignominious collapse.

The cycle formed the stuff of which history was made. Polybius, the sober, businesslike second-century BC Hellenistic historian, says that, in his time, “men turned to arrogance, avarice and indolence [and] did not wish to marry. And when they did marry, they did not wish to rear the children born to them except for one or two at the most.” And he goes on: “When a state has escaped many serious dangers and achieved an unquestioned supremacy and dominion, it is clear that, with prosperity growing within, life becomes more luxurious and men more tense in rivalry about their public ambitions and enterprises.”

The historian Livy, who lived about the time of Jesus and experienced the empire’s power at its height, says that Rome was “struggling with its own greatness.” And the poet Juvenal, a century later: “we are now suffering the calamities of a long peace. Luxury, more deadly than any foe, has laid her hand upon us, and avenges a conquered world.” Previously, he adds, success in life depended on military excellence. Now it led through some rich woman’s vulva.

After some time, this can imply that we never again want sex as frequently as we once did. order levitra downtownsault.org Compromised systems react more dramatically to the cheapest price for viagra stimulation of such a pure, organic source of caffeine. sildenafil 100mg price We even encounter stress everyday of our lives. Three out of five people will be lowest price on cialis difficult to maintain an erection, which lowers their self-esteem, because they always seem to be losing the battle.

Some of these thinkers and doers also proposed solutions. Lycurgus prohibited his Spartans from using gold and silver and made them lead lives so austere that they have become proverbial. Plato wanted his imaginary state to avoid external trade, as far as possible, so as to prevent it from growing luxurious. Interestingly, both of these also emancipated women. The former gave them much greater freedom than any other Greek city-state did. With the result, Aristotle says, that they became licentious and utterly useless. The latter liberated them from the need to look after their children, thus putting them on an equal footing with men in everything but physical strength.

Isocrates, the fourth century BC Athenian statesman, argued that, if Athens wanted to avoid repeating the cycle that had led to the ruin of its first empire, moderation and benevolence were the right tools to use. Three centuries later Cicero, the Roman orator and statesman, did the same. Polybius on his part claimed that Rome made war on the Dalmatians in 150 BC because “they did not at all wish the Italians to become effeminate owing to the long peace… [and] to recreate, as it were, the spirit and zeal of their own troops.”

In 101 BC Metellus Numidicus, censor and therefore in charge of Roman public morality, held a famous speech. The Republic, he said, was short of military manpower. But the solution was not to open the legions to property-less men as Marius had suggested. Instead he demanded that upper- and middle class men should share the burden, marry and have children. The title of the speech? De ducendis uxoribus, “about leading (marrying) women.”

Nor is the softening effect of wealth and civilization by any means the only topos around. One very widespread topos is the story of the helpless young woman who is waked up by prince charming (Snow White, Sleeping Beauty). Another, that of the prodigal son who, after many years of wandering, returns to his desolate father, mother, or girlfriend (Peer Gynt; Ruby Murray, “Goodbye Jimmy, goodbye”). Yet another, that of the noble loser who, having fought bravely, goes under through no fault of his own but maintains his dignity to the end (Spartacus, Robert E. Lee, Erwin Rommel). You get the idea.

Admittedly, all of these and many others are topoi. But that does not mean they are not true to life. To the contrary: it is precisely because they are often true that they developed into topoi and grew as popular as they did.

Food for thought here, no doubt.