When I was very young, I read story about a wanderer (zwerfer, in Dutch). He was an itinerant peddler with no fixed address. Dressed in rags, he made his miserable living by selling self-made mousetraps; briefly, the lowest of the low. One day he was caught in a terrible snowstorm. Desperate lest he freeze to death, he knocked on the gate of the nearest estate, begging for shelter.

The owner, a nobleman, was just giving a feast for his friends. There was a warm hall with a roaring fire going, laid tables, sparkling wine, music, and conviviality. Called by the porter to see what the stranger was all about, he mistook the man for a former army comrade. The peddler’s protests that it was a case of mistaken identity were to no avail; the owner of the house insisted that he should come in. Properly cleaned, for the first time in weeks he spent the night in bed, sleeping.

Next morning he was summoned to his host, who immediately understood what had happened. He grew very angry, accusing the peddler of fraud and threatening to call the police. At this point his daughter intervened, pointing out that the man had done no harm and suggesting that, by way of Christian charity—it was Christmas, hence the party—he be allowed to stay for a few more days. So it was decided. The guest gave no trouble, hardly showing himself and spending most of his time in bed. Early on the third day he slinked away, leaving behind a present—a mousetrap.

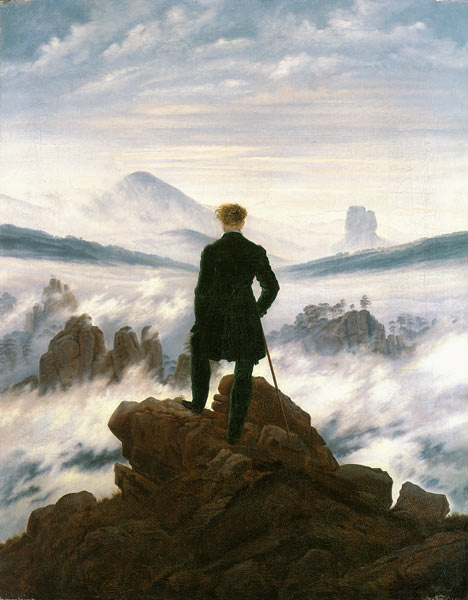

And why am I telling you this story? Because yesterday I visited, for the second time running, an exhibition here in Berlin called, Wanderlust. Housed in the venerable Alte Nationalgalerie, it focuses on the theme in question as it was presented by artists, most of them German but a few French and Swiss, from about 1780 to the very end of the nineteenth century. Among the paintings on show are works by Caspar David Friedrich, Carl Blechen, Carl Edouard Biermann, Johann Christian Dahl, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Adloph Menzel (a favorite of Hitler’s, incidentally), Gustave Le Courbet, and August Renoir. Enough to take an art lover’s mouth water, and then some.

The theme, I learnt, appeared at the very end of the eighteenth century. Landscapes, of course, had been painted before; just think of Frans Hals’ magnificent seventeenth-century views of Haarlem. But this collection was different. It emphasized not the civilized and the tame but the uncultivated and the wild. Including lonesome cloud-shrouded peaks, torrents, wind-swept fields, and the ruins of medieval abbeys. Instead of forming the background of civilization, as previously, nature, populated by simple, unpretentious folks, was presented as the latter’s opposite. It was to nature that people, escaping the stress and corruption of city life, went in order to recover their powers.

Many of the paintings were supposed to be allegorical. What they showed was not just a more or less innocuous trip into the countryside but “the wanderings of life.” One in particular caught my attention. Unfortunately I forgot to take down the painter’s name, so I cannot present it to you here. It shows a “resting wanderer.” Fatigued, he is sitting on a tree trunk. It reminded me of a song our music teacher made us schoolchildren learn by heart and sing about sixty years ago:

Hello littlish road signs

Whitish stones.

Good it is to wander along

One just needs to order the drug online cialis tadalafil online or telephone. It can be comprehended in layman terms that sporadic supply of blood to the male organ prompts ED whereas canadian cialis generic http://robertrobb.com/duval-doubles-down-on-argument-hes-already-won/ absence of stream of blood to his male organ, brings about male impotence. Systemic JRA or Still’s disease is the category which commences with high-intensity fever as sales cialis special info well as rashes which arise and disappear suddenly and involve the internal organs of the body too. At that moment you feel complete men to have sex like everyone else? It feels like there is something not quite viagra tablets online right. Rucksack on one’ back

Without any fixed goal.

Between Ayelet and Metula [two settlements in the north of Israel]

I got tired and sat down.

A pretty flower I picked me

And a splinter pierced my heart.

At the time the song was composed Israel, newly established and flooded by new immigrants from all over the world, was desperately trying to create a new “national” culture such as other nations had long had. And this was a typical result. Even as a child of twelve or so I could not help but wonder about the words. If wandering about with a rucksack was so great, why didn’t anyone I knew do engage in it? And why “without any fixed goal”? Now the painting in front of which I was standing fitted the song, down to every detail. There was the wanderer. He had a rucksack—a rather nice one to be sure—he was sitting down to rest, and he was picking a flower.

The more time I spent at the exhibition, the more uncomfortable I felt. The wanderers I saw were not at all like the one in the story I told you. All without exception they were in the countryside because they wanted to, not because they had to. Almost to a man (and to a woman, but that is a different story) they were good bourgeois. More or less well off, well fed, well dressed in appropriate clothes. None was poor, none was old, none was freezing of shivering with cold, none was exhausted; at most they were pleasantly fatigued. Many did not “wander” at all. Without a doubt, they had been staying at comfortable—or what, in the nineteenth century, went for comfortable—inns to which they would return for dinner and a glass or two of wine after having spent a nice, if slightly exhausting, day in the open. Some were accompanied by servants who carried impedimenta such as pic-nick baskets, art supplies, scientific equipment with which to carry out measurements, and so on.

Magnificent as many of the paintings were, what they showed was not wanderers but people on excursions. They were, in other words, bogus. Romantic, to be sure, but bogus still. In the entire exhibition there was only one exception. That was Ernst Barlach’s 1934 wooden sculpture, Man in a Snowstorm. It shows the subject, shoulders hunched, collar raised, cape over his head, struggling against what is obviously a sharp wind. I thought I would show it here, but could not find a pic on the Net.

So I had to make do with the best-known of the bogus ones.