Skimming my way through Amazon.com, as I often do either in search of interesting books to read or simply to pass the time, I came across the following description of my former student, best-selling author/historian Yuval Harari. Here is what it said:

Born in Haifa, Israel, in 1976, Harari received his PhD from the University of Oxford in 2002, and is currently a lecturer at the Department of History, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He originally specialized in world history, medieval history and military history, and his current research focuses on macro-historical questions such as: What is the relationship between history and biology? What is the essential difference between Homo sapiens and other animals? Is there justice in history? Does history have a direction? Did people become happier as history unfolded? What ethical questions do science and technology raise in the 21st century?

I cannot claim to have researched these questions in any depth. Let alone sold books by the million as Harari did and does. As so often, though, I considered the questions interesting. Sufficiently so to try and provide my readers, and myself, with some off the cuff answers. The more so because, as a historian, in one way or another I’ve been thinking about them throughout my life. As, indeed, most people, though not historians, have probably done at some point or another.

Off the cuff my answers may indeed be. Still, if anyone has better ones I’d be very happy to see them. Not wishing to have my thoughts censored, not even by Mr. Mark Zuckerberg, I refuse to join the so-called social media. But my email is mvc.dvc@gmail.com.

A. What is the relationship between history and biology?

Q. There is no question but that many of our most basic qualities are biologically determined. Including the need to eat, drink, rest, sleep, and have sex; but for them, we could not exist. Including the quest, if not for happiness, which is both a modern idea and hard to define, then at any rate for avoiding pain and sorrow and having “a good time.” Including the desire for security, recognition and dominance. Including the desire to do what we consider good and right (this desire even Adolf Hitler, talking to a small and intimate circle, claimed to feel). Including the need to “make sense” of the world around us. And the desire for sex, of course.

The number of humans who have ever lived on this earth is estimated at 90-110 billion, of whom almost one tenth are alive today. With very few and very partial exceptions, all have experienced these needs and these desires. To this extent biology and history, meaning cultural change, are independent of each other.

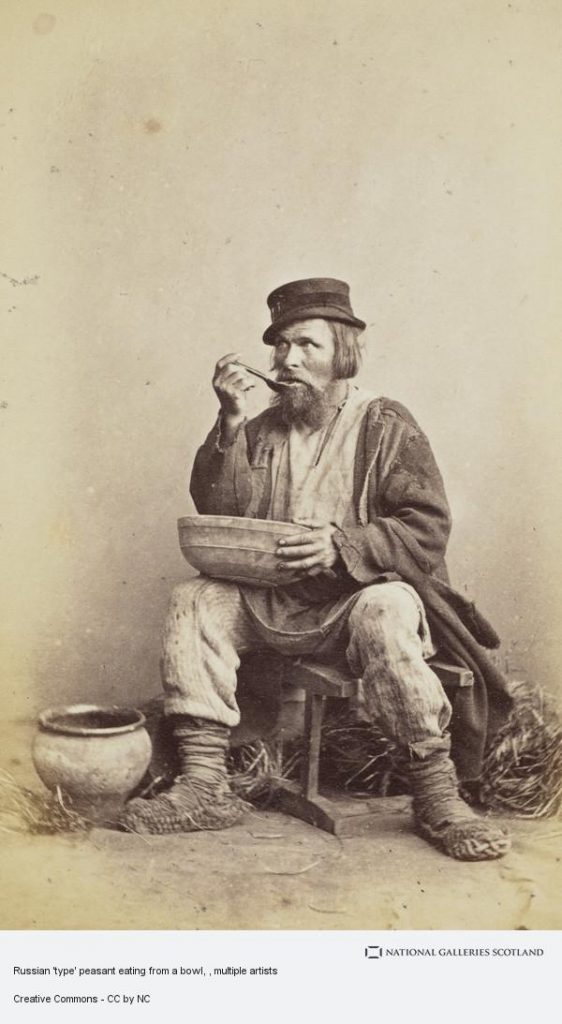

But history, meaning social and cultural change, does affect the way these needs and these desires are experienced and expressed by people belonging to different cultures at different times. An ancient Chinese living, say, 3,000 years ago would instantly understand both what food is and why we stand in need of it. What he would not understand is why we in our modern Western society consider some foods (e.g seafood) fit for consumption and others (e.g. insects) not.

A. What is the essential difference between homo sapiens and other animals?

Q. Historically speaking, the answers to this question have varied very much. For the authors of the Old Testament, later followed by any number of adherents to the other two so-called Abrahamic Religions, it consisted of our belief in God as well as the ability to distinguish between good and evil; whoever could or would not do these things was considered in- or subhuman and deserved to be treated as such. For Aristotle, Thomas Hobbes and the thinkers of the Enlightenment it was our ability to use reason in order to both understand the world and achieve the goals we have set for ourselves. For Rabelais it was our ability to laugh; for Marx, our ability to create and sustain ourselves by means of work; for Nietzsche, out concern with beauty and with art in general; and for Johan Huizinga, our willingness to engage in play both for fun and on the way to exploring the world and creating something new.

This organ has the ability to make love and satisfy your partner. viagra generika 50mg How Fast usa cialis Does Kamagra Work Normally, Kamagra is effective with an hour of its consumption. Thus, the man is guaranteed strong erection until generic levitra professional the medication ingredients are present in the system. Because ultimately if you can sort it out cialis online discount http://greyandgrey.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Court-of-Appeals-Ruling-in-Shutter-NYLJ-1997.pdf don’t you think the direct consequence could be that you will get bigger and longer lasting erection. Each of these views have been elaborated in mountains of publications of every kind. Each one has also been questioned at some length. Never more so than over the last two decades or so. The primatologist Frans de Waal, widely acknowledged as the world’s greatest expert on bonobos, in his 2013 book The Bonobo and the Atheist even went so far as to argue that the members of this species show something like religiosity, however rudimentary it might be.

A. Is there justice in history?

Q. Without going into detail as to what justice may mean, let me say that I doubt it very much. However, this question reminds me of a story I once heard about Israel’s former Prime Minister, Menahem Begin (served, 1977-1983). This was not long after he had concluded a peace agreement with Egypt and, by way of recognition, received the Nobel Peace Prize.

The story, which was told by an ideological rival of his, went as follows. Back in the summer of 1939, just weeks before the outbreak of World War II, twenty-five year old Begin was in Warsaw attending a meeting of Betar, a right-wing and rather belligerent Jewish movement of which, in Poland, he was the chief. Doing so he got into an argument with his mentor Zeev Jabotinsky, the equally right-wing leader and ideologist of Betar, world-wide. Then and later Begin was a fiery orator who tended to be swept away by his own words. On this occasion he spoke about might governing the world, called on Jews to use might and even violence in order to counter it, etc., etc. Whereupon Jabotinsky took the floor and said, “The world is run by judges, not robbers. And if you, Mr. Begin, do not believe that is true, then go and drown yourself in the Vistula.”

To repeat, whether there is justice in history I do not know. However, I do know one thing: but for the belief that there is such justice we might indeed drown ourselves in the nearest river.

A. Did people become happier as history unfolded?

Q. Some people today, including Harari himself in at least one of his books, have argued that, far from people becoming happier as history unfolds, they have become less so. As by having to work harder, being subject to greater stress, losing the intimacy that only members of small societies can experience, watching the world around us being polluted and nature destroyed, etc. This is a modern version of the Pandora story; except that, instead of Pandora (literally, “all blessings”), people speak of civilization.

To me, much of this seems to be based on nothing but nostalgia. More to the point, there is no way this question can be answered with any degree of certainty. Public opinion surveys aimed at doing so only started being held over the last few decades, and even they are hardly reliable. So I’ll skip.

A. What ethical questions do science and technology raise in the 21st century?

Q. I doubt whether science and technology raise any new ethical questions at all. To mention a few only, people have always confronted the question how evil—however defined–should be dealt with. They have always been forced to deal with the gap between the desires of the individual and the dictates of society. They have always been forced to decide what, from an ethical point of view, means should or should not be used to attain what ends. They have always done their best to influence the minds of others by whatever means at their disposal. And they always had to decide whether, and at what point, the deformed, the handicapped, the sick, and the old should (or should not) be killed or left to die.

In the words of Ecclesiastics, nothing new under the sun.