Eighty-four years ago in 1939, almost to the day, World War II broke out. Twenty years ago in 2003, again almost to the day, I gave a the following interview on the topic to the right-wing German news magazine Focus. Comments, welcome.

FOCUS: Professor van Creveld, why did Hitler attack Poland?

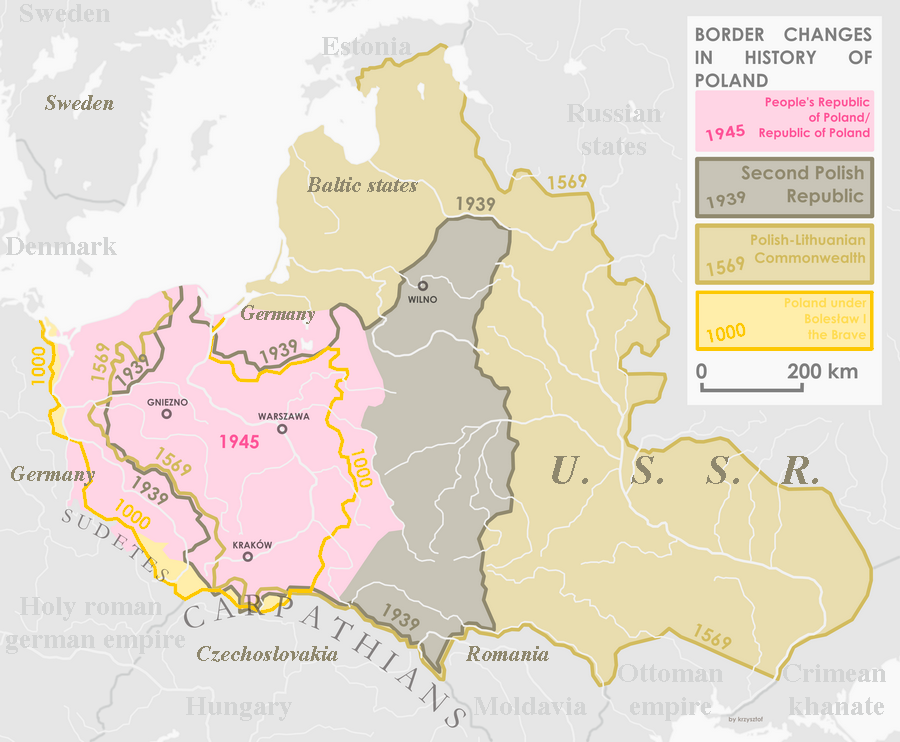

MvC: There can be no question but that one of Hitler’s primary objectives had long been the revision of the Versailles “Diktat” by returning to Germany the territories it had lost to Poland after World War I and adding to them if possible. This in turn was to be the first stage in the realization of his long-term plans to acquire Lebensraum for the German people. Yet the timing of the attack seems to have been determined by a different factor. Ever since 1937, when he was 48 years old, Hitler had looked at himself as a man past his prime. He believed that, health-wise he only had limited time left to carry out his plans.

FOCUS: Why did Stalin attack Poland?

MvC: That is very simple. Before 1918, much of Poland had belonged to Russia. In that sense, Stalin was doing no more than take back what was his in any case.

FOCUS: But together they unleased World War II. Right?

MvC: That is a way to look at it. But you could also argue that it was Britain’s guarantee to Poland that did the trick. Before the guarantee was given, Stalin feared, not without reason, that he might have to face Hitler on his own. After the guarantee he knew that this would not be the case. This left him free to conclude the non-aggression pact with Germany, which opened the road to the war.

FOCUS: Did Stalin deliberately wait for two weeks so as to make Hitler bear the full burden of having unleashed the war?

MvC: I am unaware of any historical source that makes this point; considering that he once said that “gratitude [and presumably other moral qualities as well] is something suitable for a dog”, I think it unlikely. Probably he needed some time to prepare and, cautious as he was, he also wanted to see what was happening first.

FOCUS: You say that Hitler attacked because he wanted to rectify the loss of territory Germany had suffered under the Treaty of Versailles and, if possible, acquire more. Yet in the documents of the German Foreign Ministry the words “encirclement” and “threat” keep appearing, Polish politicians often expressed their aggressive designs on Germany, and indeed the idea that the Polish-German border should run along the Oder goes back as far as the 1920s. Given these facts, would you say that Poland must bear part of the responsibility for the outbreak of the war?

MvC: The Franco-Polish Mutual Assistance pact dated to 1925. Ten years later, any significance it had ever had was nullified by the conclusion of the German-Polish Nonaggression Pact. Next, on 28 April 1939, Hitler cancelled that pact almost by a slight of hand, simply saying that “the basis on which it rested” no longer existed. One may accuse the Poles of many things. However, except for insisting on their territorial integrity in the face of Hitler’s demands and threats I do not see how one can blame them for the outbreak of World War II.

FOCUS: However, there is also a statement by Hitler, dating to the spring of 1939, in which he said that all he was trying to do was to apply some pressure to Poland over Danzig. That apart, though, he was prepared recognize Poland’s border; “he would not be the idiot who would start a war over Poland.” What did he mean by that?

MvC: At about the same time, Hitler also told his generals that “further successes in Europe without bloodshed are not possible”. So I would not attribute too much weight to this statement or that; the fact is that, having dismissed the nonaggression pact with Poland, Hitler staged a border incident (the occupation of Gleiwitz radio station) on 31 August 1939 and went to war early on the next day.

FOCUS: Was Poland ready for war?

MvC: This is a strange story indeed. By one account, weeks before the war a Polish general in Warsaw told a French delegation that, in case hostilities broke out, the French should worry about their eastern border while they themselves marched on Berlin. If that is true, then rarely in history can any military have overestimated itself to such an extent.

FOCUS: This confirms a statement by the Polish ambassador in Berlin, Jozef Lipski. Just one day before the outbreak of the war he said he did not have to worry about negotiations with Germany, given that Polish troops would soon be marching on Berlin. Did the Poles believe Britain and France would immediately come to their aid?

MvC: The Poles seem to have understood that the British and French could no longer avoid their obligations, and in this they proved right. However, they proved very wrong in estimating their own capabilities. In any case, as I said, it was not they who started the shooting war.

Had there been no Western commitment, would the Poles have accepted Hitler’s demands and would the outbreak of war on 1 September have been avoided? Perhaps. Would that have been better for the world? I doubt it.

FOCUS: During the years after 1939 Hitler revealed himself as a criminal, automatically causing his proposals to be discredited. However, this was 1939. The return of Danzig, an extra-territorial motor- and railway across the Polish Corridor, and a long time agreement concerning the border between the two countries. Would you say that, right form the beginning, these demands were illegitimate?

MvC: First, I hope you agree with me that Hitler was a criminal long before 1 September 1939. Second, what do the terms “legitimate” and illegitimate” mean in this context? If Hitler’s demands were legitimate, then so, for example, was Clemenceau’s suggestion in 1919 that Germany be dismantled by taking the Rhineland and perhaps Bavaria away from it. Perhaps the only thing wrong with that proposal is that it was never carried out!

FOCUS: Supposing the world “legitimate” is out of place, do you think that for any German to seek a revision of the Treaty of Versailles was “normal” and indeed to be expected?

MvC: Normal? With Pontius Pilatus, I answer: what is normal? Perhaps you are right: the victors of 1919 should have anticipated that no German government could live with the terms they imposed. Either they should have relaxed them, or else they should have followed Clemenceau’s ideas.

In fact, they failed to do either and fell between the chairs. By this interpretation, they did in 1945 what they should have done twenty-six years earlier.

FOCUS: Did Polish abuse of the German minority in the Corridor play a role in Germany’s decision to go to war?

MvC: Yes, clearly, but perhaps more as an excuse than as a real cause. In any case I doubt whether it was for Nazi Germany, of all countries, to complain about the way minorities were treated.

FOCUS: How strong was the Polish army??

MvC: The Poles’ main problem was not the number of troops, nor their training, nor their motivation. It was the absence of a modern industry that could have provided them with modern arms. To this were added a hopeless geographical situation and Stalin’s stab in the back.

FOCUS: Is it true, as the German Center for Political Education maintains in one of the books it promoted, that the attack on Poland was “the opening stage in a war of extermination”?

MvC: From everything I have ever read it would seem that Hitler, while determined to destroy first the Jews and then uncounted numbers of Russians, had always known that the most drastic measures would only be possible under the cover of war. So the answer is, yes.

FOCUS: Did the Wehrmacht in Poland wage a war of extermination against the civilian population?

MvC: No. But it certainly stood by and even provided support as the SS did so.

FOCUS: Did you visit the exhibition, “Germans and Poles”, in Berlin’s Haus der Geschichte?

MvC: Yes, I did.

FOCUS: Do you think the exhibition provides the visitor with a good idea of what took place?

MvC: The answer is both yes and no. I thought that the parts dealing with World War II were very good—it is impossible to exaggerate the misery that the German occupation forces inflicted on the Polish people during that period. On the other hand, I thought that everything before that was presented in a very one-sided way. It was as if, starting with Frederick the Great, the Germans had always been criminals and the Poles, angels. If I had been a German, this part of the exhibition would have made me extremely angry.

FOCUS: The fact that, during World War II, Germany committed untold atrocities in Poland is beyond doubt. However, Polish efforts to drive Germans out of Poland began much earlier. So why, in your opinion, why wasn’t this fact mentioned in the exhibition?

MvC: If you want to compare Polish atrocities with German ones, then I do not agree. If you want to say that the Poles were anything but angels, then I have already said what I think.

FOCUS: But do you agree that the organizers of the exhibition, in emphasizing German mistreatment of Poland, should also have devoted at least some space to the Poles’ treatment of ethnic Germans?

MvC: It is as I told you; if I were a German, parts of this exhibition would have made me very angry.

FOCUS: Looking back from the perspective of 2003, you could argue that, of all the states involved in unleashing the war, it was Poland that gained the most. The Soviet Union no longer exists and Russia’s border has been pushed 1,000 kilometers to the east. The British Empire no longer exists. Germany lost a third of its territory. France remains France. By contrast, the poor abused Poles have reached the Oder-Neisse frontier. Danzig has become Gdansk and Upper Silesia belongs to Poland. The irony of history?

MvC: May I tell you a story? My late father in law, Gert Leisersohn, was born in Germany in 1922. His father had fought for Germany in World War I and was wounded, yet in 1936 he and his family had to flee for their lives, going all the way to Chile. He once told me that, on 1 September 1939, he felt that while he hated war as much as anybody else, he was very happy that this one had broken out because it was the only way to get rid of Hitler.

FOCUS: Are you saying that anyone who fought Hitler’s Germany was automatically and completely in the right?

MvC: Do you know a greater wrong than Auschwitz?

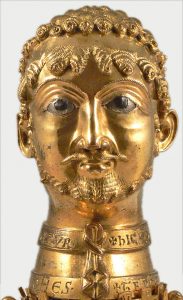

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.