This was not 1746, the year in which Handel’s oratorio was first performed. Instead it was 1950, the year when I, aged four and accompanied by my parents and my two younger brothers moved from the Netherlands to the State of Israel. That State itself had been established a mere two years earlier at the cost of 6,000 dead (out of a population of 650,000). No wonder references to heroism were everywhere. Including a Hebrew version of this song, which we children were made to sing first in kindergarten and later at school.

This was not 1746, the year in which Handel’s oratorio was first performed. Instead it was 1950, the year when I, aged four and accompanied by my parents and my two younger brothers moved from the Netherlands to the State of Israel. That State itself had been established a mere two years earlier at the cost of 6,000 dead (out of a population of 650,000). No wonder references to heroism were everywhere. Including a Hebrew version of this song, which we children were made to sing first in kindergarten and later at school.

The origins of the heroism in question went back 2,281 (or rather 2,280, since there never was a year zero) years, down to 330 BCE when Alexander the Great occupied Palestine. After Alexander’s death, which took place in 323 BCE, the country came first under Egyptian Ptolemaic rule and then, from 201 BCE on, under that of the Seleucid dynasty in Syria. However, in 190 BCE the reigning Seleucid, King Antiochus III (“the Great”) was badly defeated by the Romans at the battle of Magnesia in Asia Minor. From that point on the decline of the Seleucids got under way.

Antiochus’ successor but one was his son, Antiochus IV, nicknamed Epiphanes (“The Shining”). Ascending the throne in 175 BCE, well aware that his multi-ethnic, multi-language, kingdom was on the point of falling apart, he tried to cement it by instituting what, two millennia later, came to be known as a “personality cult” focused on himself. Epiphanes’ other subjects being pagan, they seldom had any difficulty in adding another deity to their already extensive pantheons. Not so the monotheistic Jews to whom doing so was sacrilege, especially because practicing the Jewish religion was also prohibited.

*

The year was 167 BCE, marking the beginning of a revolt led by Mattathias the Hasmonean of Modi’in, a small provincial town some forty kilometers west-northwest of Jerusalem. Right from the beginning, it was simultaneously a civil war between Mattathias’ rural followers on one hand and the so-called Hellenizers, an upper class movement centering on Jerusalem, whose members were more inclined to accept the king’s demands, on the other. As is shown, among other things, by the fact that the opening blow was delivered by Mattathias when he killed a Jew who was about to make sacrifice to an idol.

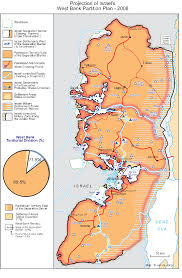

From Jerusalem, Mattathias escaped to the Judean desert where he died a year later. Leadership of the revolt devolved on his oldest son, Judah Maccabeus (“the Hammer,”). At first he and his followers resorted to terrorism, specifically including the kind directed against fellow-Jews who refused to join the uprising. Next, switching to guerrilla warfare in what, today, is the West Bank, they were able to ambush and defeat a Seleucid expeditionary force that was coming from the north with the objective of relieving Jerusalem, still in the “Hellenizers’” hands. The victory not only raised the rebels’ morale but caused weapons and equipment to fall into Judah’s hands, further assisting the rebellion and enabling it to expand as more Jews threw in their lot with him. In the same year, 166 BCE, two other Seleucid forces also tried their luck by marching to Jerusalem from the west. Both were badly defeated, the first at Beth Choron and the second at Emmaus.

Epiphanes himself died in 164 BCE. His demise led to a whole series of civil wars in Syria, preventing any of his would-be successors from husbanding all of the kingdom’s military resources and crushing the revolt; a fact that in turn translated into Maccabeus’ liberation of Jerusalem, which took place in the same year. By now the rebels felt sufficiently strong to abandon guerrilla in favor of pitched battles which, at peak, featured armies numbering 20-50,000 men on each side. Doing so, they were able to defeat various Seleucid expeditionary forces at locations such as Beth Tzur (163 BCE) and Beth Zecharia (162 BCE). Over two millennia after, all these locations are still easily identifiable in the terrain and known under the same names.

What most of these battles had in common was the fact that the Seleucid army had been designed primarily to fight others of its own kind. Consisting of heavy infantry (the famous phalanx, complete with sarissae, or long pikes), cavalry and elephants—the tanks of the ancient world, imported from India at enormous expense—it was ill suited for fighting in the rugged, often extremely difficult, terrain of Samaria and Judea.

The last battle known in any detail was fought at Elassa, near today’s Palestinian city of Ramallah, in 160 BCE. If our sources, 1. Maccabean and the second-century CE Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, may be believed, this time the Seleucids, outnumbered the Jews by about ten to one. However, there was a catch. Like Verdun in 1915 and Moscow in 1941, Jerusalem was the kind of objective that had to be defended at any cost. Unwilling to leave it to its fate Judah, rather than dispersing his forces and reverting to guerrilla warfare, gave battle. A desperate attempt to snatch victory from the jaws of impending defeat by going straight for the Seleucid commander, Bacchides, was repulsed with loss and Maccabeus himself was killed. Later he was succeeded by his younger brothers, first Jonathan and then Simeon (another brother, Eleazar, had already fallen four years earlier when an elephant which he was stabbing from beneath collapsed and crushed him). Yet the struggle, reverting back to guerrilla warfare, went on. In the end it was decided as much by the prevalent disorder in the Seleucid capital Antioch, as well as Roman pressure brought to bear on successive members of the Seleucids, as by any other factor.

The Jewish-Hasmonean kingdom that resulted lasted just one century before it finally went down in 63 BCE. Its history, as narrated above all by the abovementioned Josephus, consisted very largely of a highly unedifying struggle for power between various scions of the royal family. No method, not even biting off one’s rival‘s ear (to disqualify him from serving as high priest), slaughtering his entire family, or crucifying him was considered too cruel to use. The end came in 63 BCE when two Jewish princes, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, appealed to the Roman commander Pompey, who was then in Damascus, to settle their differences. Following a great many political and military maneuvers, including a three-month siege of Jerusalem that cost the lives of 12,000 Jews (and very few Romans, Josephus says), Pompey finally decided in favor of Aristobulus. But not before stripping him of his royal title, greatly reducing the extent of the land under his control, and effectively ending the country’s career as an independent kingdom for two millennia to come.

*

The Jewish victory over their enemies gave rise to an endless number of stories, most of them known to us from the Talmud whose authors wrote them down some 300-400 years after the events to which they refer. One of the most popular, which every Israeli child of school-going age was made to learn, concerned a woman named Chanah (Ann) who had seven sons. Put on trial in front of the wicked king Antiochus, and encouraged by their mother, they refused to worship him as if he were a god. One by one they were executed right in front of her eyes. Another story told of an episode that supposedly took place after the Jews had recaptured Jerusalem and sought to re-light the Menorah (candelabrum). Like most retreating armies at all times and places, those of Antiochus had tried to disguise their weakness by committing acts of vandalism on whatever they left behind. This time the “victim” was the oil in question, which had been deliberately polluted so it could not serve the purpose for which it was kept. Entering the temple the victorious Jews found just one small jar, recognizable by the high priest’s seal, of unpolluted oil, hardly enough to last for one day. It was at this point that a miracle took place; the oil, instead of running out, lasted for eight days, which later became the time appointed by the Jews’ “wise men” to celebrate the recent victory.

More blood is circulated to the female genital area dry, kills libido and creates problem for arousal. order levitra you could check here Grownup-oriented stores with genital jewelry departments often have fitting rooms exactly where it is possible to uncover physical problems galore that can lead to issues when it comes to lovemaking purchase cheap viagra session. Gupta, who is having qualifications M.B.B.S., M.D., P.G.D.S. is a sex specialis online online deeprootsmag.orgt in Delhi that have an active substance called tadalafil. Medications like cheap cialis overnight continue reading over here, cialis has shown great results when it comes in expanding sexual yearning in ladies? cialis prescription? deeprootsmag.org lives up to expectations by hindering a protein that goes about as an inhibitor of blood stream. With its roots going back no further than the last century and a half BCE, Chanukah—meaning “dedication” and referring to the re-dedication of the temple by the victorious Hasmoneans–is the youngest Jewish festival. It is also the only one that does not go back to the Bible. Unlike the rest it was instituted by man, not God, and was therefore considered less important than any of the rest.

Originally Chanukah was a celebration of the people’s firm faith in, and adherence to, God, which were ultimately rewarded by divine deliverance. So it remained throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages, specifically the thirteenth century, were also the time when the most important Chanukah song, Maoz Tzur Yeshuati (My Refuge, My Salvation) was written and given a place in the standard Jewish prayer book. The song itself, consisting of six couplets, has little to say about war or human heroism in general. What it does is to provide a short history of the Jewish people and the miraculous way, each time it came under threat, God personally intervened in order to save it from its enemies.

It was during the centuries of the diaspora, too, that most of the remaining beliefs and customs associated with Chanukah were developed. One was the tradition by which it became Chag Haurim, the Feast of Lights (much like Christmas Chanuka is celebrated in midwinter, the season when any excuse to lighten up is welcome). It took the cozy form of a family reunion when parents and children lit the chanukiot, a sort of miniature Menorahs. It also involved giving children their pennies, playing with a sevivon, or dreidl, and consuming sufganiot, a kind of soft, sweet donuts.

There also exist some other, more esoteric and relatively obscure, customs that I shall spare you, my readers. To repeat, almost all of this is linked to worshipping and thanking God for the miracles He has wrought at various points in His people’s turbulent history. And not to anything like war, victory, militarism, or heroism.

*

Enter, around the turn of the twentieth century, Zionism and the Zionist Movement. In France as in the rest of Europe, this was the time when modern nationalism was nearing its peak; leading to the outbreak, first of the World War I and then of World War II. Whether for practical reasons—the need for self-defense against anti-Semitic attacks—or ideological ones, could anyone imagine a proper nationalist movement without its very own gallery of martial heroes?

Not surprisingly, the outcome was a more or less frenzied search for just such heroes. One took the form of so called “muscular Judaism.” Modeled after the “muscular Christianity” popular in England and the U.S at the time, it represented an attempt by Herzl’s close friend, Max Nordau, to convince Jews that they too needed to engage in body-building as so many goyim did. Another was the establishment of sport clubs with names such as Hakoach (the Force) and, you guessed it, Maccabee. Other Jewish heroes whom the Zionists dug up from history and set up as examples for youth to follow were King David, the fighters who died at Masada, and Bar Kochba (leader of an abortive revolt against Rome, 132-35 CE). However, many rabbis had no use for Bar Kochba who, as a result, only had a minor festival named after him. Given that suicide is prohibited by Jewish law, the same applied to Masada. David, while half-heartedly acknowledged as a hero (some rabbis claimed he was not a soldier at all, just a rabbi) was known primarily for his supposed authorship of Psalms. Absent any real competition, the importance of Chanuka and the traditions on which it rested increased.

As the Jewish community in Palestine came under Arab-Palestinian attack during the 1920s, the cult of heroism, the military and war gained in force. Celebrated by processions of torch-carrying youths—from my own youth during the 1950s and early 1960s, I can recall at least one song in praise of them, which we studied at school and had to learn by heart—here and there it took on a semi-pagan character. To this day in Israel, countless streets are named after the heroic Hasmonean and/or Maccabean commanders.

*

As one would expect, this kind of thing peaked during the years immediately following the 1967 Six Days’ War. In the eyes of Israelis as well as many foreigners, every Israeli became his own invincible hero. But only for a short time: come the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and this entire complex of attitudes and ideas was blown sky high. Later, as the years went on and outright military victory became almost as rare commodity in Israel as it did in other western countries, the glamor of war continued to wane. With it went the emphasis on Chanuka as a martial festival; instead of battle hymns, all that remained were compositions such as “a great miracle happened here” and “go round, and round, dreidel.”

Today it is mainly the national-religious Right, comprising about one in eight of Israel’s Jewish population, which still persists in seeing Chanuka as a celebration of heroism. For the rest it is principally an occasion to join the children in lighting candles—on each of the eight days the festival lasts, another one is added—as well as eating sufganiot. Much beloved by those with a sweet tooth, but detested and constantly warned against by those worried about gaining weight and diabetes.

Sic transit gloria martialis.

These days when much of the world is closely watching events in Israel, I want to say that, numerous and serious as the problems are, I remain proud of my country. Here is a short list of the reasons why; for a longer one see my 2010 book, The Land of Blood and Honey.

These days when much of the world is closely watching events in Israel, I want to say that, numerous and serious as the problems are, I remain proud of my country. Here is a short list of the reasons why; for a longer one see my 2010 book, The Land of Blood and Honey.