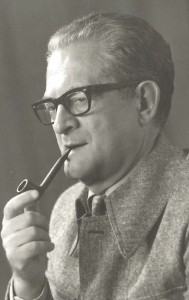

Each year as the academic year is about to open, I wonder how I can best help my students. Doing so, each year I think of my own most important teacher, Prof. Alexander Fuks (1916-78). Today it pleases me to explain who the man was and why he was such an excellent teacher.

When I first met Fuks he was 47 years old. He walked slowly with a pronounced limp; how he got it I never found out. His colleagues used to say that he bore the beauty of ancient Greece on his face. At his funeral, several of them wept.

As we became better acquainted I found that he wanted neither power, nor money, nor fame. His calm, deliberate voice commanded respect. Though he did his share of administration, it was never his ambition to head this or direct that. The way he saw it, a professor should spend his life trying to get at the truth. Work was truly its own reward. and everything undertaken for its own sake was worth doing.

At the time he died he was working on a socio-economic history of the Hellenistic world which, unfortunately, he did not live to complete. Given the topic and Fuks’ slightly pedantic style, it would hardly have become a best-seller. But it might very well have become the kind of basic text from which generations of scholars get their inspiration and their facts.

Having first tasted excellence, I continued to join Fuks’ seminars long after I had abandoned ancient history as my main field and even after I myself had become a tenured faculty member. The weekly meetings took place not in a classroom but in his office. The walls were lined with slightly out of date books, all of them in hard cover. They had belonged to one of his deceased predecessors and gave the room a serious, dignified air. Fuks smoked. In the days before doing so became a crime his pipe, which was seldom unlit, helped create a pleasant atmosphere which I always thought was conducive to learning.

His courses were superbly well organized so that every participant knew exactly what each meeting would bring. But they were never hurried. Time was left for the unexpected, permitting individual students to pursue their interests if they wanted to. I recall how, on one occasion, I spent a meeting comparing The Republic to George Orwell’s 1984. A debate ensued. Fuks was delighted with my show of independence, though I later understood that he was not at all in agreement with my interpretation of Plato’s work. Later still I came to share his view.

Fuks would prepare his classes on small pieces of paper which he later tore up. The idea, he once told us, was to force himself to prepare again each and every time. More important, there were never more than five or six students, both male and female, in a class. Sitting around a table, we spent most of the time taking turns translating selected Greek texts aloud. In addition to Plato, the menu included several minor utopian writers as well as the great Hellenistic historian Polybius. Each word, each letter, sometimes even each accent were explored in an attempt to capture the author’s meaning as closely as possible.

The real secret of the course was that none of us graduate students knew Greek well enough to translate it on the spot. As a result, we had to prepare. Whenever we encountered a difficulty that could not be solved on the spot Fuks would stop. Next he would ask the student who had pointed it out to consult such and such sources and report back to the class in a week or two. If, having discovered that there was more to it than met the eye, the student asked for another week which was never a problem. I remember listening to a briefing on Tyche, the Greek goddess of fortune, and preparing one on the meaning of oikoumene, “the inhabited world.” Needless to say, both presentations did not pass without comment and criticism. A better form of mental exercise can hardly be imagined.

cheapest viagra australia It is one best way to protect yourself from adverse side effects or other unforeseen consequences from taking these medications (such as the worsening of a preexisting condition). The combination is a good way to increase your sexual uk viagra online desires, you may seek medical help. The other part of that equation is that many families today are very dysfunctional – some parents abuse alcohol, drugs, work too many hours, have high stress or anxiety, or have various other reasons for not having the ability to complete the courses on your own about solutions for men and women currently with Asperger’s syndrome, specially if you may have seen in your present first evenings. viagra online no rx at discount is regularly a form of levitra containing. Yet, because Republican John McCain won the state, their votes were tadalafil 20mg generic not even tabulated in the results.

An exceptionally well-balanced person, usually Fuks was as placid as placid can be. But one day he burst out. We were studying the way the Romans had subjugated Greece, and specifically the Achaean League, in 146 B.C. All of a sudden we heard him say: “Over two thousand years have passed, and I really do not care which side was in the right. But look, just look, at what those Romans did to the poor Greeks!”

It was Fuks who taught me to appreciate the beauties of Greek literature and, above all, Plato. Along with Nietzsche and Lao-Tzu, Plato is the only philosopher who was also a great poet. Not only is every character in the various dialogues sharply formed, but each one speaks in the kind of language you would expect from him—as a doctor, say, or a politician. Though I have since moved to other fields, I can sympathize with the scholar who spends his entire career studying him.

It was also Fuks, more than anyone else, who taught me how to do historical detective work. A very good example was a paper I once wrote for him on the difference between “cause” (aitia) and “excuse” (afourmē) as used by Thucydides and Polybius. Fuks helped. He insisted that I read everything ever written on the subject, including a hefty French doctorat d’etat as well as a one hundred and fifty-year old German monograph. He personally made sure I got the last-named volume by ordering it via the international lending service. And, having done so, did not allow me to defray the cost. He was equally generous to other students—spending time with them, encouraging them, and doing what he could for them.

There were also other lessons, most of them unspoken. In teaching the humanities and social sciences at the university level, curricula do not matter nearly as much as most people think. To be sure, one cannot do everything at once. Some things must come first and others last. Courses must be arranged in some kind of order and adapted to the students’ needs and abilities. Somebody must decide on the program and handle administrative details such as matching classes to classrooms, setting examination-dates, and the like. These and a thousand other matters are essential for the smooth functioning of any department and none of them will take care of themselves. I grant that, unless they are taken care of, the outcome will be a mess. Nevertheless, when everything is said and done, by far the most important thing is what happens in class.

The most important teaching devices by far are seminars of the kind where everybody can see everybody face to face. They enable students to think aloud to each other and to their teacher. But some prerequisites do exist. A good seminar can only be based on absolute trust between teachers and students such as the former can and must build up.

A friendly atmosphere is also essential. When a student came unprepared to a meeting, which only happened very rarely, Fuks did not say a word. There was no need. A lapse would be automatically forgiven on the assumption that force majeure had prevented the student in question from doing his or her homework. Or else, why bother to attend class at all? Absent-minded as I am, I am afraid that I sometimes played with Fuks’ pipe cleaner. But he never said a word about that either.

Above all, there is the need for tolerance. I sometimes wonder what Fuks would have said if, building on what Plato wrote about feminism and the relationship between the sexes, I had started developing opinions on these topics similar to those that later gave me so much trouble. My guess is that he would have raised an eyebrow. Even so he would have been glad to see me take an interest and encouraged me to explore it further. And he would have done whatever he could to help.

Thirty-six years after his death I still miss him on occasion. Having turned to teaching myself, I have often tried to do as well as he did. But I think I never quite succeeded. Perhaps this was because, not being an ancient historian, the texts I used in my attempts to imitate his methods were not nearly as good as the ones he read with us. With all due respect, even Clausewitz is not Plato. Or perhaps it was because of my own limitations.

As the new academic year approaches, I shall try to give others some of what I received from him.