As others beside me have noted, one of the most astonishing things about the war in Ukraine is the fact that cyberwarfare does not seem to be playing a major role in it. To be sure, there has been what one source calls “a steady drumbeat of attacks, including disinformation campaigns, distributed denial-of-service attacks that temporarily knock websites offline, and ‘wiper’ attacks, which infect computer networks and render them inoperable by deleting all files. But no question of malware taking the place of bullets, shells, rockets missiles and bombs, small and large. No talk of countrywide water, gas, electricity, communication and transportation systems being knocked out by all kinds of oddly-named devices used by either side. Instead, old-fashioned kinetic warfare seems to be not only alive but kicking out ferociously in every direction at once. Just take a look at images filled with wrecked Russian tanks, or, on the other side, some photographs of what much of Mariupol now looks like.

As others beside me have noted, one of the most astonishing things about the war in Ukraine is the fact that cyberwarfare does not seem to be playing a major role in it. To be sure, there has been what one source calls “a steady drumbeat of attacks, including disinformation campaigns, distributed denial-of-service attacks that temporarily knock websites offline, and ‘wiper’ attacks, which infect computer networks and render them inoperable by deleting all files. But no question of malware taking the place of bullets, shells, rockets missiles and bombs, small and large. No talk of countrywide water, gas, electricity, communication and transportation systems being knocked out by all kinds of oddly-named devices used by either side. Instead, old-fashioned kinetic warfare seems to be not only alive but kicking out ferociously in every direction at once. Just take a look at images filled with wrecked Russian tanks, or, on the other side, some photographs of what much of Mariupol now looks like.

Why the role of cyberwar seems to be so much smaller than expected I do not know. Judging by some articles on the topic that have surfaced on the Net, neither do others. Based on what decades of study have taught me about the relationship between technology and war, though, personally I think there are several possibilities. First, it may be that the difficulties an attacker faces in effectively penetrating an enemy’s computer network in such a way as to make a difference are greater than many experts had thought. Second, the defenders on both sides may have prepared much more effectively than anyone expected. Third, there is the question of secrecy. Meaning that, if there has ever been a field in which holding one’s cards, whether offensive or defensive, close to one’s chest is vital, this is the one.

Such being the situation, I want to provide a fourth explanation. Many of you will be familiar with the name of Giulio Douhet (1869-30). Douhet was a World-War I Italian general originally commissioned into the artillery. In 1922 he published Il dominio dell’aereo, almost certainly the most famous volume on the topic ever written and a cardinal point of reference for practically everything that has been written on it since. However, it is neither this book nor Douhet’s influence on airpower that I want to discuss here. It is, rather, his theories on the way technology, specifically including technological innovation, and war interact. In 1913 Douhet, while still only a major on the general staff, produced an article on that question. It is that article which I have used as my guide.

So here goes.

Stage A. A new technology is introduced. Normally this is done by the inventors and manufacturers who hope to make a profit and turn to the military as a potentially very large customer; also, perhaps, by all kinds of visionaries out to make their ideas known. The idea meets with skepticism on the part of defense officials and officers who, often not before being repeatedly harassed, are sent to examine it. Having conducted a more or less thorough investigation, they submit their report in which they claim that the new technology is simply a toy and will never amount to much. Good examples of the process are provided by the Zeppelin, heavier than air aircraft, the submarine, the torpedo and the tank, all of which were invented before 1914 and all of which initially met this fate. There is even a story about a British regimental commander who, upon receiving a couple of machine guns, told his men to take the “bloody things” to the wings and hide them.

Stage B. The manufacturers do not give up. Having perhaps enlisted (bribed?) a visionary or two, and directing at least some of their efforts at the public at large, they continue to push. Sometimes by offering their invention to an enemy of the country they first approached. Sir Basil Zaharoff, though not an inventor but a merchant, was the undisputed master in this game, selling warships to both Turkey and Greece. Slowly and gradually, the military undergo a limited shift. They are now ready to find out whether there is any way in which they can incorporate the new weapon or weapon system into the existing organizations without, however, acknowledging the need to change that organization in any fundamental way. At times they even start adopting a new invention in order to prevent change; as the German Luftwaffe did when it developed the V-1 as a counter to the early ballistic missiles favored by the land army and as the US Army did with the Redstone missile during the 1950s. Other good examples of the attempt to pour new weapons into old organizations are, once again, the heavier-than-air aircraft and the submarine. And the aircraft carrier, of course.

Stage C. Quite suddenly, the wind changes. As older officers die or retire, younger ones—those in charge of the new technologies and in favor of them—start shouting their virtues from the rooftops. The more so if the technologies in question can be shown to have played a key role in some recent war. Military history is making a fresh start! They say. The new technologies are about to take over! Everything else is ripe for the dustbin! And so on and so on. Douhet himself set the example. By the time he wrote his book he had convinced himself that armies and navies were about to disappear and that airpower, like the Jewish God in one of the prayers addressed to him, “all alone would rule in awe.” Similar claims on behalf of aircraft were made in the US by General Billy Mitchel; whereas in Britain another officer, Brigadier general John Fuller, was doing the same on behalf of tanks. Nowadays they are being made on behalf of artificial intelligence and autonomous killing machines among other things,

Stage D. It becomes evident that, useful as the new technologies are, they do not provide answers to all problems. As invention is followed by counter-invention, pilots find that they cannot simply bomb the hell out of whomever they want at any time they want. Submariners discover that, without support from the air (later, satellites), their ability to find their targets is very limited. Tanks are threatened by anti-tank guns and missiles and are, moreover, only useful in certain, well-defined, kinds of terrain. Carriers, even such as rely on nuclear propulsion, have to be escorted by entire fleets of anti- aircraft and anti-missile destroyers, anti-submarine destroyers, and supply ships. And autonomous killing machines have a tendency to break lose and kill indiscriminately. Briefly, the new technologies must be integrated with everything else: strategy, tactics, command and control, logistics, intelligence, doctrine, organization, training and what not.

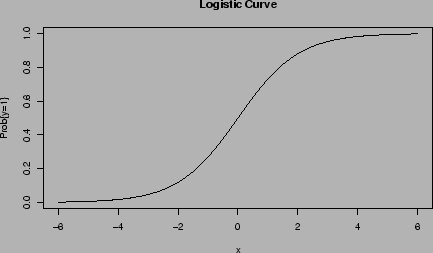

Stage E. Following the usual logistic curve, shown above, the process of reorganization has been driven as far as it will ever be and is now flattening out. Advanced, even revolutionary, weapons and weapon systems have become an integral part of the forces. Perhaps, as in the case of carriers from 1941 on, their lynchpin. By this time most of those who initially opposed the changes are gone. A new generation of officers has risen and takes things as they now are for granted.

Judging by what little is known of the role cyberwarfare is playing in Ukraine, we seem to be taking leave of stage C. Could it be that we are now entering stage D? And if so, what new gizmos will the future bring?