There are two cardinal reasons why President Putin has almost certainly lost the war he launched over a month ago. Both are as old as history, and both were set forth by Clausewitz around 1830. First, a military operation, large or small, is much like pouring water from a bucket (the metaphor is mine, not Clausewitz’s); the further away from its point of origin it flows, the more momentum it loses and the more vulnerable it becomes to counterattacks directed both against the spearheads and against the attacker’s lines of communication. Just think of Napoleon in 1812. Having invaded Russia with 600,000 men, by the time he reached Moscow he only had 100,000 left; all the rest had either perished by battle, disease and fatigue or been left in the rear to garrison key positions there. 100,000 troops were not nearly enough to force a decision, let alone hold the country down. And so all it remained for him was to retreat.

The second and even more fundamental reason is that time works against the attacker. Why? Because, under most circumstances, conquering and appropriating is harder, and requires greater force, than holding and preserving. An offense that does not attain its objective—from the attacker’s point of view, that would mean a better peace—within a reasonable amount of time is certain to turn into a defense. Think of Hannibal in 218-17 BCE, think of Hitler in 1941-42. Again this applies to any military operation, large or small, old or new.

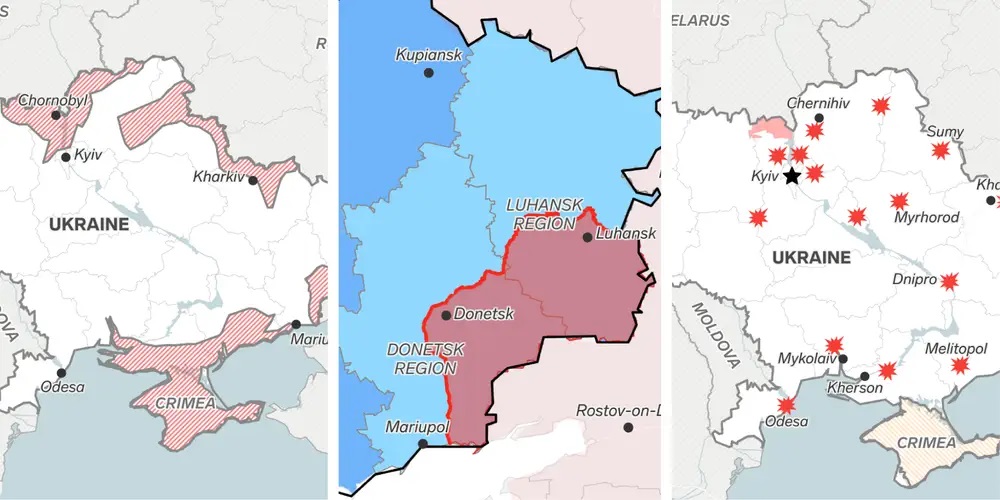

So far, Putin’s war has proceeded in four stages. First, a combination of geography and numerical superiority enabled his forces to operate on external lines and invade Ukraine from four different directions (northwest, north, east and south) at once. Second, enjoying both numerical and technological superiority, and some logistic problems notwithstanding, those troops pushed the Ukrainians aside and reached the outskirts of the most important Ukrainian cities such as Kharkov, Kiev, Kherson, and Mariupol (important because of its command of the Sea of Azov as well as the road from the Donbas to the Crimea) and put them under siege. Third, especially at Kherson and Mariupol, they tried their hand at urban warfare. Only to find, as countless others before them have also done, that such warfare tends to be very bloody and very destructive. The difficulty of obtaining intelligence, the excellent shelter cities provide to those who defend them, and the way rubbish-filled streets canalize and hamper the attacker’s movements all contribute to this result; between them they cause cites to swallow up armies the way sponges take up water.

Fourth, and rather predictably, the Russians switched from attempts to capture Ukrainian cities to subjecting them to artillery bombardment. Just as, some twenty years ago, they did in Grozny. In Kherson and Mariupol the tactic worked, at any rate up to a point. However, Kiev and Kharkov are much larger than either of those. Besides, Ukraine itself is a large country with many urban areas, large and small. Not even the Russian army, famed for its reliance on artillery, has enough guns to take them on all at once; whereas doing so one by one will require enormous amounts of time which, for the abovementioned reasons, Putin simply does not have.

Fifth, the offensive having exhausted itself, stalemate will set in if, indeed, it had not done so already. Stalemate having set in politics, which right from the beginning played a very important role, will start playing an even more important one. All sides will have a strong interest in ending the war. Hence attempts will be made to do so on terms all of them —Russia, Ukraine, NATO—will find more or less acceptable or at least capable of being presented as such.

Just what the final settlement will look like is impossible to say; most probably, though, it will include the following elements. First, there can be no question of doing away with Ukraine as an independent country and nation. Second, there will be no subservient government in Kiev as there is in Minsk. Third, Russia will make no important territorial gains beyond those made in 2014 and even its ability to hold on to those is in some doubt. Fourth, Ukraine will not officially join NATO, let alone have NATO forces stationed on its territory; but other, more limited, forms of cooperation between the two entities will certainly be established and maintained. Fifth, Putin may, but not necessarily will, lose his post.

Finally, never forget that war, though it makes use of all kinds of physical assets such as numbers of troops, weapons, equipment, roads, communications, topographical and geographical obstacles, and so on, is a human drama above all. As such it is critically affected by every kind of human, often incalculable, drives and emotions; which, collectively, shape the fighting power of both sides. Taking all this into account, it becomes only too clear that anything that can be said about the way future campaigns will develop is no more than what Clausewitz calls a calculus of probabilities.

So it has been, and so it will remain

The war in Ukraine goes on and on. Though analysts are as numerous as flies on a heap of you know what, the truth is that one knows how it is going to end. Such being the case, I want to put my latest thoughts on record.

The war in Ukraine goes on and on. Though analysts are as numerous as flies on a heap of you know what, the truth is that one knows how it is going to end. Such being the case, I want to put my latest thoughts on record.