Despina Stratigakos, Hitler at Home, Yale University Press, Kindle ed., 2015

Despina Stratigakos, Hitler at Home, Yale University Press, Kindle ed., 2015

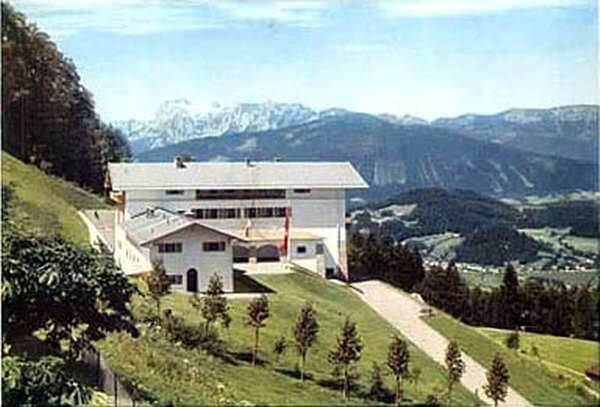

Ms. Stratigakos, a professor at the University of Buffalo, is a historian who knows her way about architecture and design. Or perhaps I should call her an architect and designer who knows her way about history and how to write it. In this book, one of four she has authored (and two I’ve read), she treats us to a tour of the Berghof, Adolf Hitler’s retreat in the Bavarian Alps. The outcome is as fascinating as books of this kind can be.

The story starts in 1927 when Hitler, then 38 years old and the leader of a small but noisy party in the German parliament, was introduced to the area by one of his adherents. So much did he like the house, known as Haus Wachenfeld after the owner, that he decided to rent it and make it his vacation home. Not long thereafter he bought it, putting it on his sister’s name so as to avoid paying taxes. From this point until the summer of 1944, when he left it for the last time, his fate and that of the Haus were inextricably linked.

Not that the Berghof, (translatable as either Mountain Farm or Mountain Court), as Hitler renamed it, was ever his only home. Not long after he first visited Berchtesgaden, as the area was and still is called, he also acquired a large and comfortable flat in the center of Munich. The city where, the four years he spent in the trenches apart, in which he had lived from 1912 on and in which the National Socialist Party was born some seven years later. Following his appointment as Chancellor in January 1933 he also had at his disposal an entire complex (or, following Hindenburg’s death and the merger of his post with that of the president, two complexes) of buildings on the Wilhelmstrasse, in Berlin’s government quarter. Prof. Stratigakos describes both of these complexes in considerable detail right down to location of the vestibules and the toilets as well as the colors used in each room.

All this is interesting enough. Prof. Stratigakos, however, focuses her attention on the Berghof. Why? Because, much more than the other two quarters the Fuehrer occupied, Hitler used it for propaganda purposes to celebrate his lifestyle and cement his bonds with the German people over whom he ruled.

Needless to say, Hitler was not alone. The list of those who aided him in this effort is a long one. The first was Paul Troost, the architect who presided over the first expansion and modernization of the Berghof in 1932-33. After his death, which occurred in 1934, the work was taken over by his widow Gerty; most of the interior decoration of the house, including such details as the selection of colors, curtains, furniture, decorative articles, tableware, and so on can be traced to her influence. Heinrich Hoffman, Hitler’s official photographer, who took thousands of pictures of the man and his home and selected hundreds of them for publication in every kind of medium available at the time. Nazi bigwigs such as Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach who wrote adulatory texts to accompany the photographs. And Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, who saw to it that the material should be distributed all over the Reich.

From the hands of these and countless others, the popular image of the Fuhrer emerged. No lover of great cities but a simple resident of a simple house in a simple village in a simple, if exceptionally beautiful, district. Relatively poor (one of the few criticisms I have of Prof. Stratigakos’ work is the emphasis she puts on the sums spent on the Berghof; whatever else, they did not compare with the 160 or so castles belonging to the Hohenzollern family).

No snob, but “our Hitler” as Goebbels liked to call him; a man among men (and women who, from beginning to end, were among his greatest admirers) with whom he was on easy terms. Dressed in simple clothes; no elaborate headdress, no rows of glittering if often meaningless medals on his chest. Good with women whom he treated with an old-fashioned sort of respect reminiscent of his Austrian homeland. Good with children whom he invited to parties and fed with cakes. Good with dogs which he was always trying to train. And possessed of a small weakness (a sweet tooth) that would make those in the know smile indulgently.

The last large expansion and renovation of the Berghof took place in 1937-38. By that time it was well on the way in being turned from a relatively modest private residence into a kind of second capital where the owner spent as much of his time as he could. Important guests—including Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, former British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George, and Heinrich Himmler, the SS commander responsible for carrying out the Holocaust—visited. Important officers, e.g some 200 generals on the eve of the invasion of Russia, received their marching orders. With the Fuehrer’s brutal deputy, Martin Bormann, in charge, paved roads, guest houses, barracks for the SS guard, vast underground storerooms and communication corridors appeared as if by magic. So did the houses of Hitler’s paladins including Goering, Speer, Goebbels, and Bormann himself. The demands of total war—especially in terms of raw materials and workers—did something to slow the building process. However, until July 1944 when Hitler left his house for the last time, it never stopped.

To repeat, I found almost all of this fascinating. Still the author will have to forgive me for writing that the most interesting, as well as the most important, chapter is the last: containing, not detailed descriptions of the Berghof, nor the use that was made of it for purposes of propaganda and bolstering the regime, but the fate that overtook it after the war’s end. Having already been heavily bombed by the RAF, first it and the surrounding area were occupied and looted by American troops. Not always with success, since secret storerooms and corridors are being occasionally discovered right down to the present day. Then what remained of the house was dynamited along with most of the remaining structures. Then the entire area, some 150 square miles in size, was returned to the Bavarian Government.

Then the debate what to do with it got under way in earnest. Who, if anyone, should be allowed to visit the remnants of the various structures and if so, under what conditions and for what purposes. Whether there should, or should not, be a visitor center and, if so, what it should tell visitors. How to avoid turning the area into a sort of ghoulish holiday park (complete with a miniature gas chamber, perhaps?). How to prevent it from attracting Nazis, Neo-Nazis, extremists, and ordinary right wingers. The kind who would gather to worship the man who liked to describe himself as the greatest German of all times.

Stuck in Germany’s throat, Hitler and everything pertaining to him is. To quote a Hebrew phrase that seems singularly appropriate, neither to swallow, nor to puke. And so, as then Chancellor Helmut Schmidt warned his countrymen decades ago, it will remain for a thousand years to come.