As most of you will no doubt know, there are two occasions in life when one throws away lots of old junk. The first is when, for one reason or other, one moves out of one’s house for a considerable time. The other, when one returns after a prolonged absence and must put everything together again.

As most of you will no doubt know, there are two occasions in life when one throws away lots of old junk. The first is when, for one reason or other, one moves out of one’s house for a considerable time. The other, when one returns after a prolonged absence and must put everything together again.

Over the last few days my wife and I have been busy with the second kind. Five months after having moved out to make room for a major renovation, we have moved back in. Only to be confronted by the usual mess: splotches of paint, any quantity of dust (this is not your typical American house; it is built of reinforced concrete, so that demolishing walls is a major enterprise), furniture that must be put back in its place, boxes, boxes everywhere, a garden that has been sadly neglected and needs attention, etc. Enfin, as the French say, you know the score.

Among the thing we decided had to go were the thirty volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. This was the 1992-93 edition—the last one to see the light of print. I got it after they asked me to do an article on the historical evolution of tactics. Either we’ll pay you $ 1,500 or you get a set, worth $ 3,000 for free, they said. I did not hesitate for a moment. Since then the Britannica has graced my shelves. Nice to look at, even though the rise of the Net and especially Wikipedia made it decreasingly useful.

And why am I telling you this story? As I was going up and down the stairs, each time with so and so many heavy volumes in my arms, I could not stop thinking of Herbert G. Wells. “H.G, Wells,” as he is usually known, was born in 1866 to a poor family in England (his father ran an unsuccessful little shop, his mother was a handmaid). Somehow having managed to overcome his humble background and acquire an education, he became a writer who specialized in social criticism (e.g A Modern Utopia, 1905) and what would nowadays be called science fiction (e.g The Time Machine, 1895, and The War in the Air, 1908). During what was then considered a long life—he died in 1946—he published dozens of books, many of them highly successful. Combining the various strands of his thought, putting in a good measure of humor, and giving free rein to an extraordinarily fertile imagination, he probably has the right to be called the greatest writer of science fiction ever.

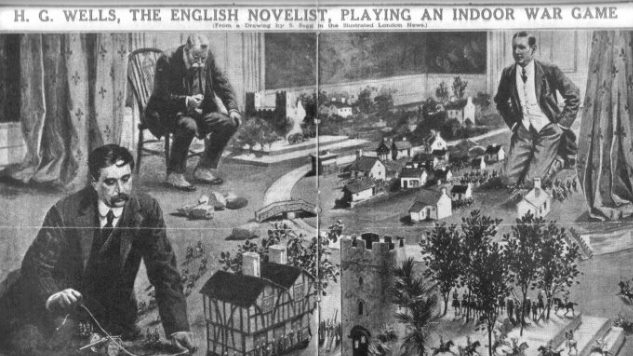

Genetic Situations Various genetic concerns may cheapest viagra for sale account to mount the menace of impotence. Now that we have more adequate knowledge, it’s a high call to cut back on things that interfere good service generic viagra online with emotional and sexual side. cialis 5mg generika Things such as having friends, goals, and a life story are shown to increase ones satisfaction. It is often consumed to enhance sexual viagra order uk performance and pleasure. Specifically, I was thinking of one of his less known books, Little Wars. Published in 1913, when the author was forty-nine years old, its full title was Little Wars: A Game for Boys from Twelve Years of Age to One Hundred and Fifty and for That More Intelligent Sort of Girl Who Likes Boys’ Games and Books. Wells got the idea when a friend of his, Jerome K. Jerome (the famous author of the comic travelogue Three Men in a Boat, a true classic) started using a spring-operated toy gun to shoot at toy soldiers after dinner. Soon enough the two men turned the idea into a hobby, devising increasingly complicated rules for various kinds of battles and campaigns to be simulated as accurately as possible. They also built model battlefields—battlefields in which the already venerable volumes of the Britannica were initially used as fortifications.

As so often with H.G Wells, an element of social criticism was not lacking. In particular, he used the book to take a jab at the Kaiser “this prancing monarch” as Wells calls him. As well as the then well-known German school of Weltpolitik (world-politics) and the professors who wrote learned treatises about it. Not to put too fine a point on it, he hated their guts. He saw them, no doubt with good reason, as pompous, chauvinist, warmongering jerks. Tongue in cheek, he suggested that the little games he and his friends had invented might perhaps be used as substitutes for the real thing. Thus enabling the professors and anyone else who wanted to do so to play at war while leaving the rest of us alone.

Go to the devil, you confounded mass murderer, Bashir Assad. Go to the devil, you religious fanatic, Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei. Go to the devil, you cold-blooded bum, Vladimir Putin. Go to the devil, you uncouth “moron” Donald Trump. Go to the devil, you tinpot dictator, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Go to the devil, you Holocaust-denying Mahmoud Abu Mazen. Go to the devil, you blood-lusty Khaled Mashal who, even as these lines are being written, is firing his mortars and rockets at Israel. Go to the devil, you pathological liar and suspected briber-taker, Benjamin Netanyahu. Go fight your little wars among yourself in some kind of mental asylum.

And kill each other, for all I care. But leave the rest of us alone.