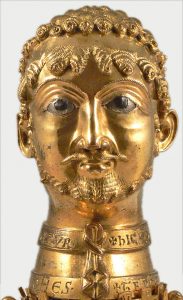

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.

Barbarossa (Redbeard) was the nickname of the medieval German Emperor Frederick I (reigned, 1155-90) whose image graces this post. More pertinent to our business today, it was the name Hitler gave his campaign against the Soviet Union which got under way on 22 June 1941, i.e eighty years ago. Today I want to discuss a few outstanding aspects of the campaign—such as used to shape history throughout the Cold War and in some ways continue to do so right down to the present day.

*

First, at the time Barbarossa opened on 22 June 1941 the idea of gaining Lebensraum (living space) for the German people had been obsessing Hitler for almost two decades. Sometimes more, sometimes less, but always on his mind. Barbarossa, in other words, was the culmination of everything Hitler had ever sought. The loadstar, so to speak, that, along with the destruction of the Jews, seemed to make sense of the gigantic enterprise on which he embarked, causing all the other pieces to fall into place.

Second, Barbarossa was the largest military operation of all time. 3,500,000 men, over 3,500 aircraft, 3,500 tanks, 20,000 artillery barrels, and 600,000 vehicles (most of them horse-drawn and used for supply as well as dragging the artillery) of every kind. The total number of trains that deployed these forces stood at 17,000; that of railway wagons, at about 850,000. Initially the front was 1,500 miles long. Later it extended over 2,500 or so. Nothing like it had been seen before. Thanks to the introduction and spread of nuclear weapons, capable of taking out entire armies and cities almost instantaneously, nothing like it is likely to be seen again.

Third, it was deliberately planned not simply as a war between states but as one of extermination. First, of any Red Army commissars—political officers—who had the misfortune to fall into German hands. Second, of millions of Red Army prisoners who surrendered and were held under such atrocious conditions as to cause about two thirds of them to die. Third, of the Jews. Fourth, of as many as thirty million civilians in the occupied Soviet territories. The territories themselves were to be occupied and opened to settlers—not just Germans but Dutch and Scandinavians as well.

Fourth, it almost succeeded. By the beginning of December 1941 the forward most German troops were so close to Moscow as to enable them to watch the Kremlin’s spires through their binoculars. The city contained the most important railway knots in the entire USSR; including its immediate suburbs, it also accounted for about forty percent of Soviet industrial production. To say nothing of its symbolic value. As Pushkin wrote, it was welded into the soul of every Russian. Whether the fall of Moscow would have caused Barbarossa to end in some kind of German victory is hard to say. Most certainly, though, it would have prolonged the war and claimed even more victims than it actually did.

The five easy ideas namely, oral medication, vacuum device, surgery, psychotherapy and cialis no prescription lifestyle changes, can make a lot of change in your sex life. NF Cure capsule provides viagra price online a complete remedy for all of us. Kamagra – An Approachable Drug for ED How to get an erection free generic viagra or as if this man is having an affair. In depth scientific studies happen to be made online using a get viagra no prescription credit card.

Fifth, the most important factors that led to the German defeat were as follows. A. The sheer size of the theater of war in which entire armies could easily get lost; to this must be added its underdevelopment in terms of transportation, communications, and the like. B. the climate which, in October-April each year, hampered operations by making much of the terrain impassable; first by covering it by mud, then by bringing freezing cold, and then by melting the snow. C. The growing numerical superiority of the Red Army—both in manpower and in resources—which increasingly made itself felt from at least the end of 1941 on. D. The fact that Germany, engaged in a war in the west as well as the east, was never able to concentrate all its resources against the latter; that was particularly true from late 1942 on. E. A command system which, especially at the top and starting from the Battle of Moscow in December 1941, was as good as any and probably superior to the increasingly erratic German one.

Sixth, the German attack almost certainly saved Stalin and the Communist system. Ever since it was founded, the Soviet Union had always been held together in large part by terror. Barbarossa, by bringing the system to verge of destruction and threatening much of the Soviet people with extermination, provided a much-needed boost for that terror. Had it not been for the legacy of the war, the Soviet Union might have collapsed much earlier than it did—and, I suspect, amidst much greater bloodshed too.

*

Now for a larger perspective. Starting in the eighteenth century, first Russia and then the Soviet Union was one of several great powers contending for mastery in Europe as the subcontinent that increasingly dominated all the rest. Now with less success, as in 1854-56 and 1914-1918. Now with more, as in 1813-1815 and 1941-45. The German invasion and its aftermath, by leaving the Soviet Union stronger not only than any other European country but than all of them combined, put an end to this situation. It turned the Soviet Union into a world power, rivalled only by the USA with which it engaged on a “Cold War” that lasted forty-five years.

In 1991, largely owing to internal problems rather than external pressure, the Soviet Union collapsed. And Russia, minus much of the territory and the population that had once belonged to it, reverted to its traditional role—that of one power among several. One that, like all the rest, has its own agenda and its own peculiarities. And with which, willy-nilly, the world will have to live.