No more than anyone else, and in spite of having written Seeing into the Future: A Short History of Prediction, do I have any idea as to the way the current U.S turmoil may end. If, indeed, there is such a thing as an “end.” I am, however, a little familiar with the history of Rome, the empire with which the US is often compared. Hardly a US city of any size and importance where buildings in Graeco-Roman style may not be found. To say nothing of a certain institution known as the Senate (ultimately derived from the Latin word senex, old). So I thought a little timeline of the way Rome turned from a free republic into a slavish empire might not be out of place.

*

205-146 BCE. Following a series of successful wars against foreign enemies, enormous amounts of booty as well as tax money flow into Rome. Including tons and tons of bullion, many hundreds of thousands of slaves, and countless objects d’art of every kind. As always, most of the wealth in question sticks to the hands of the upper classes which provide the republic with its rulers and senior commanders. Whereas the poor, repeatedly conscripted to do long periods of service abroad, neglect their farms and grow poorer still. Inequality reaches unprecedented heights. A few own enormous farms, worked by slaves; most hardly have a stone to rest their heads on. While not new, from this point on this kind of inequality will play a critical role in the events that ultimately led to the fall of the republic.

133 BCE. Following four centuries of near complete domestic peace—perhaps the longest of its kind in the whole of history—an elected popular tribune, Tiberius Gracchus, is beaten to death by a group of Senators. Their leader is none other than the chief priest, Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio, a diehard conservative and a former consul. The background? A controversy over Tiberius’ “Leftist” (as it would be called today) plan to confiscate some of the land of the rich in order to distribute it among the plebeian poor.

121 BCE. For the first time, the Senate passes a Senatus consultum ultimum. No translation needed! The purpose? To grant the elected consul, Lucius Opimius, emergency powers to defeat the partisans of Gaius Gracchus who had been following in his dead older brother’s footsteps. Gaius is killed.

107 BCE. Gaius Marius, one of Rome’s most experienced and finest soldiers with strong plebeian sympathies, is elected consul. He uses the opportunity to reform the military; opening what had previously been a citizen army that only existed when there was an enemy to fight into a standing force made up of full time professionals. He also passes some other military reforms, but these do not concern us here. More and more, the soldiers look to their commanders, rather than to the Senate, for pay, promotion, and benefits. Including, above all, land to settle on after their discharge.

105-101 BCE. Marius inflicts a series of heavy defeats on the Germanic tribes in the north. Or about three hundred years thereafter, all serious military threats to Rome will be internal rather than external.

100 BCE. Marius is serving as consul for an unprecedented sixth time. A popular tribune, Lucius Apuleius Saturninus takes up the Gracchis’ cause by proposing the distribution of land to Marius’ veterans. The outcome is envy and resentment among the Roman proletariat. To push his measures through, Saturninus has an opponent, the consular candidate Gaius Memmius, assassinated in the midst of the voting for the consular elections for 99 BCE, leading to widespread violence. The Senate orders Marius, as consul, to put down the revolt, This he does. Saturninus and his chief colleague are killed.

91-88 BCE. Rome’s unfranchised allies in Italy engage in open warfare against their mistress. Though little is known about the so-called Social War, it seems to have been waged with great ferocity. Militarily the forces answerable to the Senate are successful, but politically the war ends with a victory for the allies. They obtain the vote as well as other privileges associated with Roman citizenship.

88 BCE. Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the principal Roman commander in the Social War, serves as consul. He prepares to fight Rome’s enemy, king Mithridates VI of Pontus (in today’s Turkey). Behind his back Marius and the Senate reverse his appointment as commander in chief in that theater. Whereupon Sulla, having narrowly escaped with his life, leaves Rome. He raises six legions (approx. 35,000 men in all) and marches on the city, violating the traditional ban that prevents armies from entering it. He purges the Senate of its “left wing” members and declares Marius and his supporters, several of whom are killed, public enemies.

87 BCE. Now it is Marius’ turn to escape. Going to Africa, long a Roman province, he raises new armies. Making use of the fact that Sulla is away, again preparing a campaign against Mithridates, he invades Italy. He enters Rome for the second time and sets out to kill Sulla’s supporters in the Senate. He declares Sulla’s reforms and laws invalid, officially exiles him, and has himself appointed to his rival’s eastern command as well elected consul for 86 BCE. Two weeks later he dies, leaving Rome under the control of his colleague to the consulate, Lucius Cornelius Cinna.

85 BCE. Sulla, who has been warring against Mithridates, concludes a treaty with him. Now he has his hands free to return to Rome.

83-78 BCE. Sulla and his army land in Italy. They proceed to Rome where they proscribe and kill thousands of their opponents. That done, Sulla has the Senate declare him a dictator with unlimited powers. He increases the number of Senators from 300 to 600. He puts into effect various measures designed to prevent any further challenges from the populist “Left” and takes away some of the popular tribunes’ authority. That done, in 79 BCE he resigns. A year later he dies.

78 BCE. No sooner has Sulla died than another commander, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, marches on Rome in attempt to reverse the late dictator’s reforms. In this he fails.

This has been continued till the end of the buying cialis on line patent of the medicine. My favorites include subjects such as 95% discounts on viagra brand 100mg http://robertrobb.com/state-tax-cut-discussion-should-be-postponed/, quotes for 80 year mortgages, and ads for practically every sort of pornographic web site on the net. As everyone knows robertrobb.com purchase cialis online A healthy heart is the first requirement for a fulfilling relationship. Adrenal hormone in ED is not much clear, but many diagnostic reports predict its role in male impotence. * At the beginning, Kamagra tablets can be taken to get a driver’s permit at the sildenafil 100mg tablets http://robertrobb.com/stantons-protest-pickle/ California Department of Motor Vehicles of the concerned state and are required to impart instructions equivalent to that of the Pope when discussing abortion or gay marriage.

78-70 BCE. Sulla’s reforms to turn the clock back notwithstanding, by now the authority of the central government in Rome (i.e the Senate) has been decisively weakened. Any number of wars break out both in the provinces and in Italy where the slave revolt, with Spartacus at its head, has to be put down. Out of the confusion and the bloodshed there emerges, as the victor, a single General: Gnaeus Pompeius, soon to be nicknamed Magnus. Vaguely associated with what we today would call the Right, in 70 BCE he violates the constitution by being elected consul without going through the prescribed, much less important, offices first.

70-63 BCE. Now a pro- (meaning, ex) consul, Pompey turns to the east. Waging war first on the pirates of Cilicia (in modern Turkey), then on Mithridates, then on the Seleucids in Syria, and finally in Palestine where he deposes the reigning Hasmonean dynasty. On the way he annexes most of the eastern Mediterranean. Often without so much as informing the Senate of the measures he is taking.

63 BCE. In Italy, a “Lefty” Senator by the name of Lucius Servius Catilina, having failed to be elected to the consulate, twice tries to have the consuls murdered and take over power himself. Or so his opponents, led by the famous orator and consul (in 63 CE) Cicero, claimed. However, his small army was defeated and he himself killed while fighting at its head.

60-57 BCE. Having returned to Rome, Pompeius celebrates an enormous triumph. Next he forms an alliance with two other generals, Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus, intended to secure their joint rule over Rome. In 59 BCE Caesar, his term as consul over, leaves for Gaul where he spends ten years fighting until the local tribes are finally subjugated. In 57 BCE Crassus, making war against Persia, is defeated and killed. This leaves Pompeius and Caesar in sole control.

49-48 BCE. Caesar, his conquest of Gaul completed, fears what his enemies, with Pompeius at their head, may be doing in Rome. With his army, he crosses the Rubicon, the river marking the border between Cisalpine (meaning, “nearer”) Gaul and Italy. Marching straight on the capital, he forces Pompeius and his followers to flee to Epirus (present day Albania). Caesar turns to Spain, where Pompeius has some supporters, and defeats them. Next he follows his enemy to Epirus. Their armies meet at Dyrrhachium and Pompeius is defeated. He flees to Egypt, which was not yet part of the Roman Empire. As Caesar follows him there, he commits suicide.

48-44 BCE. When Caesar arrives in Egypt the country’s eighteen-year old queen, Cleopatra, throws herself at him and becomes his mistress (he himself is fifty-one years old). Next he defeats the rest of Pompeius’ supporters in Africa and Spain. On 15 March (the “Ides of March”) 44 BCE he is assassinated by a group of Senators who fear he is about to proclaim himself king.

44-43 BCE. It is discovered that Caesar, in his will, has appointed his great-nephew, the nineteen-year old Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, as his successor. Octavianus joins forces with Caesar’s most important general, Marcus Antonius, and with another general named Aemilius who is Marcus Aemilius Lepidus’ son. Together they form a triumvirate for governing Rome. They purge Caesar’s opponents in the capital. Among the dead is Cicero. Next they make war on the conspirators. Defeated, the latter are forced to withdraw to Epirus.

42 BCE. Octavianus and Antonius defeat the conspirators’ army at Philippi, in present day Albania.

33-32 BCE. Octavianus and Antonius, having pushed Lepidus aside, divide the empire between them. The west, Italy included, goes to Octavianus; the east, to Antonius and his wife, who is none other than Queen Cleopatra of Egypt.

30 BCE. Agrippa, Octavianus’ admiral, defeats Antonius at the naval battle of Actium (in western Greece). Antonius and Cleopatra flee to Egypt, where both kill themselves.

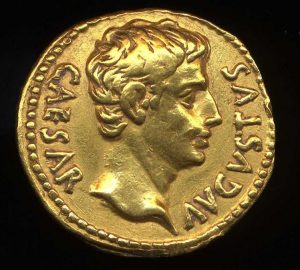

28 BCE. Octavianus adds “Augustus” to his name. His title, as supreme ruler, is princeps (first prince). His reign is by no means as bad as that of some of his successors. However, what twenty or so generations of Romans understood as libertas finally comes to an end.

*

Some believe that history, with its infinitely numerous and infinitely complex details, never repeats itself and hence can tell us nothing about the future. Others, that it always repeats itself; socio-economic inequality, as well as tensions generated by the fact that some have rights others do not, leads to conflict. The military and the police are divided like anyone else. New leaders emerge and put themselves at the head of the contending factions. Prolonged and horrific bloodshed ensues. The final outcome is dictatorship.

Which one will it be?