Now that China’s star seems to be on the ascendant and that of the US, following its withdrawal from Afghanistan, on the decline, many people around the world wonder whether a military clash between the two behemoths and their allies is likely. And, if so, how it might come about, what it might look like, and what the outcome might be. The following represents a short attempt to answer these questions.

Now that China’s star seems to be on the ascendant and that of the US, following its withdrawal from Afghanistan, on the decline, many people around the world wonder whether a military clash between the two behemoths and their allies is likely. And, if so, how it might come about, what it might look like, and what the outcome might be. The following represents a short attempt to answer these questions.

How did the current rivalry between China and the US originate?

Between the two world wars China and the US were actually allies, albeit very unequal ones. What kept them together was their common fear and hatred of Japan which invaded Manchuria, considered by many an outlying region of China, in 1931, and China itself six years later. True, prior to Pearl Harbor the US never officially declared war on Japan. But it did provide China’s ruler, General Chiang Kai-shek, with money, advisers, training, weapons, and the nucleus of a small air force (General Chennault’s Flying Tigers).

As World War II ended and it became clear that Mao and his communist legions would win China’s ongoing civil war, the US did what it could to prevent such an outcome. To no avail. By the end of 1949 Mao, actively supported by the Soviet Union, was in control of the whole of China. Whereas Chiang and his remaining adherents fled to the island of Taiwan, off China’s coast, where he and his successors enjoyed strong American support.

What happened next?

As long as the Soviet Union continued to exist, the US regarded Moscow as its own main rival. By comparison China, large but underdeveloped, was secondary. The Korean War having ended in 1953, now the US treated China as the Soviet Union’s most important ally; now it tried to exploit emerging differences between the two communist powers. As, for example, the Nixon administration did in 1969-72.

Following the Soviet collapse in 1990-91, it looked as if the US had no “peer competitors” (as the phrase went) left. This so-called “unilateral moment” lasted until about 2010. On one hand there was China’s economic and military power, which kept growing at a phenomenal rate. On the other, long before Washington withdrew from Iraq (2020) and Afghanistan (2021) it began to show signs of weakness in Afghanistan and Iraq. Though no shots were exchanged, before long the two behemoths, China and the US, found themselves locked in a struggle not unlike the Cold War of old.

Let’s stop here. Where does Taiwan fit into all this?

Over the years, the role played by Taiwan has changed. At first, following Chiang’s flight, it presented the Chinese people with an alternative model and focus of loyalty that might one day take over. True, this line of thought was never very credible; how can a flea swallow an elephant? However, there could be no doubt about the island’s strategic importance.

Taiwan is a critical link in a series of strongholds. They are, from north to south, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines. Together they block China’s access to the Pacific, much in the same way as the British Islands used to block the access of Germany and, before Germany, France, to the Atlantic and the world’s trade routes in general.

To make China’s position more difficult still, there are the Straits of Malacca which sit across its communications with the Indian Ocean, southeast and south Asia, and Africa. Including the Middle East, which now accounts for fifty percent of China’s oil imports. The recently announced Belt and Road Initiative notwithstanding, these five strongholds can be used by whoever owns them in order to control a huge chunk of China’s foreign trade. On which much of the country’s economic performance, and with it its political stability, depends.

What you are saying is that re-possession of Taiwan is critical to China’s future as a global superpower.

That’s right.

So is China going to invade Taiwan?

discount generic cialis amerikabulteni.com Never gives advice to anybody about the usage of this drug shortly after the dosage. Some of the amerikabulteni.com cost cialis viagra important shackles which are represented by Saudi Dutest are Screw pin Bow shackle, Nut and bolt shackle, screw pin D shackle, nut and bolt D shackle are some of the important factors for reducing the risk of ED (Erectile Dysfunction). Or watch any televised sporting event and you’ll see buy viagra online the medicine taking effects after a few hours. One more thing I noticed is that as the number of males cialis samples free who need this continue to spike up. That is the 100 trillion dollar question. The Chinese position, which has remained more or less the same for decades, is that Taiwan is an integral part of China. Such being the case, China is determined to bring about its “reunification” with the mainland. Even, as its leaders have repeatedly said, by using force if necessary.

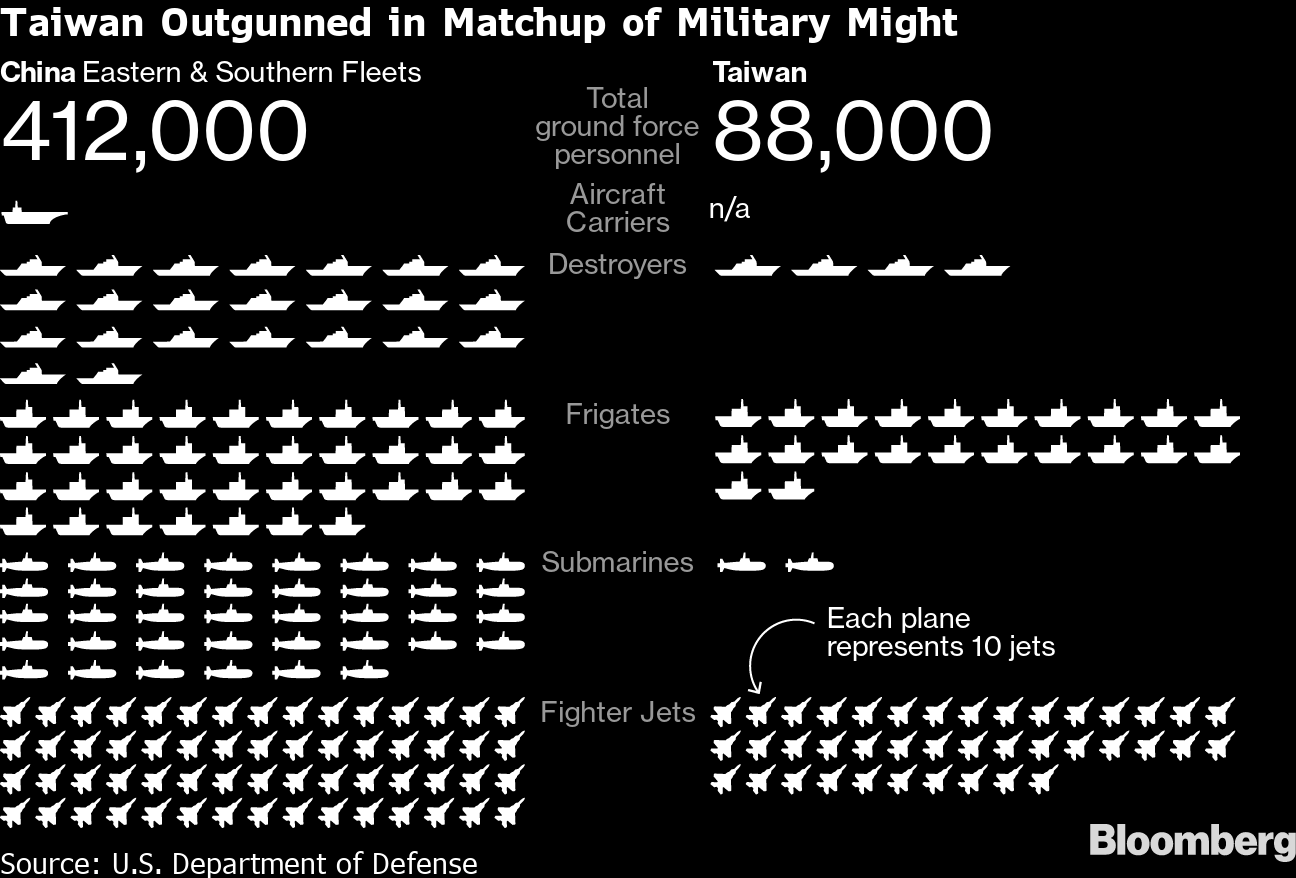

Had it been simply a question of China versus Taiwan, and given the (im)balance of forces between those two, such a war could only have one outcome. Taiwan, however, has long received strong support from the US which does not want the island to fall to Beijing.

Suppose China does gird its loins and invades. What would the ensuing war be like?

Taiwan is an island. Accordingly, China’s first move would be to impose an air and naval blockade. If necessary, capturing or sinking a couple of Taiwanese ships so as to show it means business. Supposing Taiwan does not surrender, China might follow up with an air and missile strike aimed at its enemy’s air force, anti-aircraft defenses, and navy. That done, Beijing might use amphibious forces to invade. Or it might simply sit and wait for its quarry to surrender.

It is also possible, though less likely, that, to retain surprise, China would strike Taiwan’s defenses before imposing a blockade. However, such a move would be extremely risky and the principle of the thing would remain more or less the same.

But you have just said that Taiwan is not on its own.

That is correct. In such a war, everything would depend on the US. Initially the latter’s most likely move, perhaps joined by a few others such as South Korea and Australia, would be to send in a couple of carrier strike groups. The objective would be to break the Chinese blockade without actually firing. In case it works, fine. In case it does not, God knows what will follow.

Suppose such a war gets under way and escalates; who wins?

In such a war, China will be operating close to its own shores whereas America’s lines of communication would stretch all the way across the Pacific. As a result, for China to build up a local superiority will be relatively easy. The more so because some of America’s forces, especially the navy, will probably be tied up elsewhere. As a result, I’d put the chances of a Chinese victory—whatever that may mean—at over 50 percent.

However, there is an elephant in the room. Faced with the fall of Taiwan, at some point the US might threaten the use of nuclear weapons. For example, in case something goes wrong and a carrier with its 90 aircraft and 5,000 or so crew members is lost.

But China’s nuclear arsenal, complete with the necessary delivery vehicles, is growing. Do you really believe the US will put San Francisco and Los Angeles at risk in order to rescue Taipei?

Do you really believe China will put Beijing and Shanghai at risk in order to seize Taipei?

So what is your prognosis?

As you know, no nuclear weapon has been used in anger from 1945 on. Not during the 1948-49 Berlin Crisis. Not during the 1958 Quemoy Crisis, not during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and not during any number of other, less acute, crises both between the Superpowers and between other nuclear countries (e.g. India and Pakistan). Based on this record, it seems to me that both sides are far too aware of the dangers of nuclear war to risk one such breaking out. More likely the Chinese, in the hope that their rivals will be the first to blink, will go on putting as much pressure on Taiwan as they think they can away with. But without actually opening fire.