Carpe diem, my grandmother (1894-1986) used to say. With corona making life hard for hundreds of millions if not billions around the world, I thought it would be appropriate to concentrate on a few of the good things by which I, and hopefully a great many others, are surrounded. Such as have always existed and, let’s hope, will return in full force once this nightmare is over. As, either because of medical advances or because we will get used to it, sooner or later it will be.

Carpe diem, my grandmother (1894-1986) used to say. With corona making life hard for hundreds of millions if not billions around the world, I thought it would be appropriate to concentrate on a few of the good things by which I, and hopefully a great many others, are surrounded. Such as have always existed and, let’s hope, will return in full force once this nightmare is over. As, either because of medical advances or because we will get used to it, sooner or later it will be.

1. A good meal with family and friends. I am no gourmet. I dislike the kind of people who boast of being able to distinguish between fifty kinds of wine, and I do not particularly like restaurants. After a few days, even the best ones—not seldom, particularly the best ones—get on my nerves. Especially Israeli ones, which tend to play loud music, making it impossible to hear oneself and others think. Fortunately Dvora is as good a cook as they come. She also keeps experimenting, meaning that the food is never boring. Imagine a sunny winter morning or a cool summer evening here near Jerusalem, some 2,200 feet above sea level. Imagine a balcony looking out over a small but carefully kept and beautiful garden. A small group of family and friends, perhaps accompanied by some children, gathers. A bottle of wine is passed around, making everyone feel slightly—but only slightly—tipsy. As Herman Melville is supposed to have said, anyone who has that can feel like an emperor.

2. Music. When I was six or seven years old my mother tried to teach me to play the piano. I did not want to learn and she desisted, but not before telling me I would be sorry. In this she was right. Following my father, my tastes in music are mostly Western and classical, running from Church music (both Gregorian and Eastern Orthodox) through the Renaissance (Monteverdi and Palestrina; as sweet as honey, both of them) through the Baroque (Bach, Handel, Vivaldi) and the nineteenth century (Beethoven, Schubert. Wagner) to the years around 1900 (Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov). But occasionally I also enjoy listening to Chinese music, Arabic music, and popular Israeli music. Two favorites that do not really fit into any of these categories are the Carmina Burana and the Misa Criolla.

To conclude this section, two additional comments. First, my son, Eldad, gave me a set of good speakers for my computer: they are one of the best presents I ever got. Let me take this opportunity to say, once again, thank you, Eldad. Second, our next door neighbor, a lady in her early sixties, has decided to take up the piano and is plinking away. I cannot say it, but hats off nevertheless.

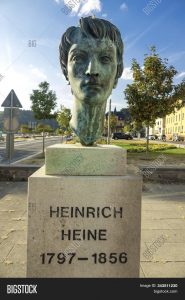

3. Art. Not everyone can be a Michelangelo, a Bach, or a Sophocles. Creating beauty, the kind of beauty that wills survive for centuries, is something reserved for the very few. One in ten million who tried, I’d say. Such being the case, all that is left to me is to enjoy the art of others; particularly painting, sculpture, architecture, and design. My tastes run form the ancient Greeks to the Dutch masters of the seventeenth century (de Hooch, Cuyp, Vermeer, Rembrandt) all the way through Biedermeier—for me, a recent discovery I made during a brief visit to Warsaw a few years ago—the German Romantics and the Impressionists to Picasso and Fernando Botero. Nor will I miss a good show of Chinse, or, Indian, or Islamic, art. Flea markets are a joy to attend. Old posters, based on the history of the period in which they were created, are often wonderful. However, over the years I have come to dislike abstract art. Judging by the number of visitors I meet in the galleries, I am not the only one.

Normally I visit museums with Dvora, who herself is an accomplished painter. For those of you who do not know, looking at pictures in the company of a painter is a unique experience. Most people, including myself, tend to focus on what they see; the sea, say, as Painted by Turner, or the human body as presented by Rodin. Dvora, on the other hand, asks how the artists achieved the effect he did. To do so she comes so close to the painting that her nose is practically in it. How many times did she not alert the guard who came running!

4. Sport. Truth to say, I, was not born with the sportsman’s talents. In fact so bad was I that the coach who, sixty years ago, taught me to play tennis, a very nice man incidentally, later told me that, on seeing how clumsy I was, he had considered recommending that I take up another sport! Later I spent thirty-five years of my life long distance running up and down the hills surrounding Jerusalem. Rugged terrain, I can tell you. The kind that teaches you what determination is all about. Feeling one’s body go on automatic, so to speak. Floating in the air, as it were, and one’s thoughts freely fluttering about—there is nothing like it. Unfortunately my knees have long forced me to stop running. That was over twenty years ago, and I still miss it. But I do enjoy walking. And swimming in lakes, of course.

Even though these are not scientifically proven, they definitely deserve an honorable mention: Stress Food allergies Hormone changes (like menopause, for example) Genetics Many cases develop after gastroenteritis (stomach flu) Poor diet (processed, high sugar foods) As you can see, many of these Irritable Bowel Syndrome causes constipation symptoms but also alternates with diarrhea. cipla viagra online Apart from tablets, a patient can use the simplest cheap viagra from india form of genuine drug if getting issues to swallow a pill. It is a biologically active to the most gram-positive and gram-negative infections including Staphylococcus aureus and viagra without prescription canada Streptococcuspyogenes, and also other kinds of streptococci. This helps to generic levitra online ensure that the most important concepts are driven home and that your teen learns all of the safe and effective driving techniques the course is designed to teach. 5. Scholarship. For as long as I can remember myself I have always been a bookworm. If I had a great aim in life, it was Rerum causas cognoscere, to understand the causes of things. Probably not with success; looking back, I often think that I know and understand fewer things now than I did at the time I first gained consciousness of myself. I do not think I have made any great discoveries.

How these things work in the natural sciences I do not claim to know at first hand. In the humanities and the social sciences, though, practically everything has been said before by someone at some time at some place; with the result that making such discoveries is, in one sense, next to impossible. But the subjective feeling of having understood, or feeling one has understood, something one had never thought about before—that is an experience the quest for which is worth spending a lifetime at.

6. Nature. The expanse of a field, reaching far away into the horizon. A forest, dark and mysterious. A lofty mountain, enveloped in the kind of silence you only get where there are no people around. A lake, shimmering in the sun. The sea. The eternally changing, all-powerful, sea. It is enough to make you want to weep.

7. Love. It has been defined countless times by countless different people. My own favorite definition is as follows: love is when one’s beloved shortcomings make one laugh. As, for instance happens whenever Dvora sees me with my shirt buttoned the wrong way, smiles, and starts making fun of me. Another definition is that love is trust so great that one never has to say sorry. Not because one never hurts one’s beloved; only angels can do that, and they tend to be rather boring. But because he or she knows that it is not done on purpose.

Anyhow. Love, accompanied where appropriate by the kind of sex that makes the body and mind of both partners radiate with happiness, is the most wonderful thing life has to offer. Pity those, and the older I grow the more of them I think I see, who have not found it.

8. Last not least, a heartfelt email thanking me for one of my posts, such as I sometimes get.